Women in stonelifting

Guest article by Jamie McGregor

Throughout my years lifting stones, I’ve often wondered: Why aren’t women doing this?

Worldwide, there are a few legends of women conquering heavy stones – like Iceland’s Húsafell stone, stones on Jeju Island, and the milk maid stones of the Faroe Islands (and more).

There are a couple of stories of women in Scottish history lifting stones, too, but in truth, they are very few and far between. The first that comes to mind is the grandmother lifting the Barevan Stone with the use of a plaid, or Clach Altruman Mor and Beag on the Isle of Coll, which were known as his and hers stones (there are more examples of his and hers stones in Ireland).

When you look at women today purely from a strength perspective – largely thanks to the growth of Strongwoman and Powerlifting – you begin to realise that some of today’s women are stronger than the young men of the day trying to attain their “manhood” back in clan times.

So why aren’t women lifting stones – particularly in Scotland? Eventually, that recurring thought got me thinking of ways to try and develop stonelifting for women to bring the ancient tests firmly into the modern day. But first, let’s look at history to try and find out why Scottish women didn’t lift stones.

History

In Scotland, from the time of William Wallace and Robert the Bruce (late 13th and early 14th centuries), through the fall of the Jacobite rebellion in 1745, and beyond the highland clearances in the early 1800s, our country was fiercely divided and a particularly brutal and tough place to live. You had to be strong just to survive.

Men had to master the art of soldiery. As a clansman, you could be called upon at any time to stave off an attack by a neighbouring clan – or an invading army for that matter. This system relied on ideas and qualities tied to masculinity, valuing physical strength, violence, and honour.1 Lifting a heavy stone was one way a man could prove his strength.

For women, it was a different story. There isn’t as much known about the typical Scottish women from the same period; research into the lives of Scotland’s women is still a relatively recent field, and the number of historical documents focusing on the average woman is fewer. But women weren’t warriors. And they didn’t need to prove their strength by lifting stones.

Above all, the Scottish wife was responsible for caring for her children and performing domestic work. Wealthier families could afford female servants to carry out domestic tasks, so the wife’s domestic role became even more important the further down her family was on the social ladder.1

Women did plenty of heavy work; they were a major part of the Scottish workforce, particularly in agriculture, since the majority of people lived at a subsistence level as farmers.1 Their heavy workload may have been greater in the Highlands where men considered agricultural work (or at least certain agricultural tasks) beneath their status.2

Some accounts say that women toiling in the subsistence economy were haggard, worn out, and prematurely aged by their labour. Recurrant illnesses and agonizing childbirth didn’t help.1 And if that wasn’t enough, between 1563 and 1736, the majority of people prosecuted for witchcraft in Scotland were women.3

Evidence of women taking part in heavy sports is basically non-existant as far as I can tell. And by the 18th century, the Scottish ideals of femininity that were gaining traction almost certainly prevented any women from taking part in them.

Looking at the evidence we have, it’s not surprising then that women probably didn’t lift stones: Peasant women were perpetually exhausted, others were constrained by feminine ideals, and the rest were prosecuted for witchcraft.4

Any documented accounts of Scottish women lifting stones are likely only because they were anomalous acts.

Society has progressed significantly since the early modern period. Despite that, it’s not uncommon to see negative opinions of women who lift weights thanks to beliefs surrounding masculinity, femininity, and strength. Perhaps those negative views combined with the false idea that Scotland’s lifting stones are all “manhood” stones stunted the growth of stonelifting compared to strength sports like Powerlifting?

The plan

To be honest, I didn’t have much of an actual plan – just a single thought leading to an action that snowballed: Wouldn’t it be great to run a stonelifting competition to hightlight women in stone?

After driving by Ballachallan Farm many times (and having a fascination with stone circles), I decided to contact the then owner of the farm, Kirsty Buchanan, who invited me for a look around. The stone circle itself was not historic in nature, but more a replica of an ancient circle that had been there in time gone by.

Anyway, we got talking and Kirsty told me she was looking to run a Tough Mudder style event on the land. I suggested a natural stonelifting competition instead, and she was excited by that.

So we put our heads together and came up with a plan to run a five event women-only stonelifting competition, partly due to logistics; we had a short time frame and it’s easier to locate and collect smaller stones.

I came up with some natural stonelifting events and created an event page on Facebook. Within a day of posting, it received 17 sign-ups!

There are the events I chose:

- Stone press for reps

- Walking stones for max distance

- Stone put

- Húsafell carry for max distance around the stone circle

- Stone load to barrel

For the next few weeks, I basically spent my time searching fields, rivers, and wherever I went just collecting suitable stones in the boot of my car. Kirsty had access to the forest and quarry behind the farm, so she picked up some stones from there, too.

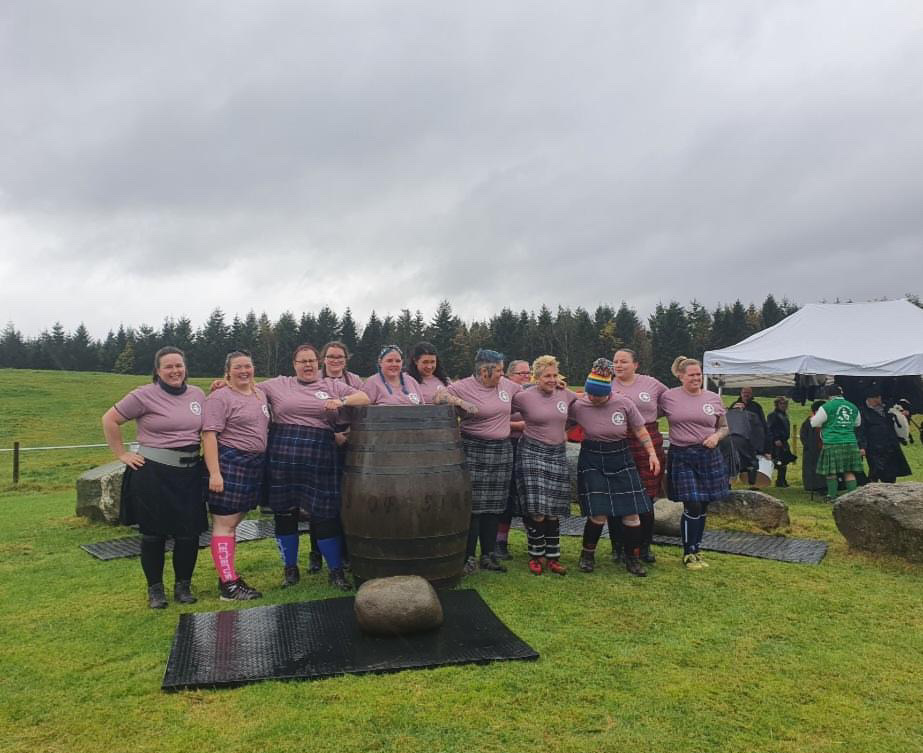

On the day, 13 ladies turned up in the rain to compete. And we even had some lifts of the Puterach Stone, which I brought along the as the guest of honour.

It was the beginning of something great!

There was some room for improvement considering this was the first competition, but the Ballachallan Games set the scene for The Mcgregor Games which have become a massive success for both men and women.

A stonelifting tour

Following on from the Ballachallan Games, I arranged a few stone tours to prove my theory. And I was correct! We saw brilliant lifts of a few historic lifting stones, including some absolute firsts.

We had Mairi Ross lifting and loading the 120kg Sheriffmuir stone onto the ancient Wallace plinth, and loading The Sadlin’ Mare and The Puterach to their plinths.

Izzy Tait loaded the Sadlin’ Mare and Puterach and performed an amazing lift of The Fianna stone, lifting it to chest!

Roni Rose became the first woman in history to chest The Glen Lui stone. And Bex Innes from Canada lifted the Sadlin’ mare to chest, too. These are just a few examples of incredible lifting that has happened recently.

After the historic stonelifting tour’s success, I decided to place some modern stones to recreate a his and hers scenario. But where? Personally, I don’t think it’s right to mess with history, so all of the established historic sites were a no-go – I feel they shouldn’t be tampered with. I also feel strongly that the term “historic” does not refer to a stone’s age, but the stone’s legacy as a lifting stone. So, in essence, once a stone has been placed, lifted, and named, its history begins.

I had already created Scotland’s heaviest stone tour, The Ochil Loop, by placing stones strategically around The Ochil hills in Stirlingshire and Clackmannanshire. It was a slightly selfish endevour to prepare myself for lifting in Iceland and Ireland, but it also meant that people could do a stone tour in an afternoon without having to drive for hours between stones. There are seven stone sites on this loop and the stones are attracting a healthy amount of visitors.

However, it got me thinking it would be ideal to place lighter stones alongside the brutes, creating an opportunity for a genuine stone tour where women and newcomers could recreate history and move stonelifting into the future.

Four of the sites already had some smaller stones nearby, so I just had to ensure they were of sufficient quality. I collected the rest from Lossiemouth beach whilst visiting my grandkids and from the stone haven of Glen Etive. Most of the sites on the loop now have a smaller stone for lifters, but there are still a couple waiting on companions.

- The No. 9 stones: 60kg, 100kg, 145kg (named after the No. 9 mineshaft on which they rest)

- The Glenochil stone: 177.5kg

- The Logie Kirk stones: 145kg and 80kg

- The Clan Macrae stones: 160kg and 85kg

- The Sherriffmuir stones of strength: 55kg, 73kg, 95kg, 120kg, 130kg, 163kg

- The Glendevon stones: 145kg and 90kg

- The Harvieston stone: 143kg

I arranged a tour of the loop in February and placed the last two stones. It became the first male and female tour with 11 lifters throughout the day. It was an amazing day and so special to see my efforts in setting it up getting such a positive response.

The Future

The future is bright for stonelifting – for men and women. People are discovering stones all over the world along with their history. More lifters are buying into the modern stonelifting sites, too.

There’s more interest in stonelifting compeititions, too. With my McGregor stonelifting games, the Donald Dinnie and Jan Todd Games, IHGF competitions, and more around the world, it’s given more people the opportunity to take part in an ancient test of strength.

My advice: Just go and try it. You might actually find something you love. Need a push? Message me on Instagram.

I wish more women would get involved in reviving this ancient cultural strength history of ours as it’s a unique and deeply fulfilling endeavour.

Author

Jamie McGregor is one of the most accomplished stonelifters in the world. He lifts historic stones almost weekly, researches Scottish stones, and hosts his own stonelifting competitions!

Contributions

With massive thanks to Jamie for sharing his story! You can follow him on Instagram.

With special thanks to Lynn Abrams for her email correspondence.

Notes

-

Dòmhnall Uilleam Stiùbhart (1999). Women and Gender in the Early Modern Western Gaidhealtachd, pg 233-235 ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Rosalind Mitchison (1983). Lordship to patronage: Scotland, 1603-1745, pg 86 ↩

-

Seventy-five per cent of an estimated 6,000 individuals prosecuted for witchcraft between 1563 and 1736 were women and perhaps 1,500 were executed. There are multiple factors that may have caused the witch trials and prosecution of so many women, but one significant factor could be the change in attitudes towards women during the period. ↩

-

While my comment here is reductionist and hyperbole, I hope it illustrates that life was obviously difficult for Scottish women and that they had more important things to worry about than lifting heavy stones. ↩

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.