Stonelifting on Jeju Island

During my lifting stone research I came across a paper from 1984 by David Nemeth discussing stone lifting on South Korea’s Jeju Island. David describes and discusses a culture that has several parallels to European stone lifting culture. This article covers much of David’s paper, but the original is well worth reading if the topic interests you.

Jeju Island

Jeju Island is a small volcanic island off the south coast of South Korea and it’s a popular tourist destination thanks to its climate and scenery. 15 million visitors pass through the island every year.

Korea’s Stone history

Stone fighting or Seokjeon ‘석전’ (literally stone battle) was a popular pastime in Korea. Originally it was a form of martial training where two teams would throw stones at each other. Needless to say, these battles were a violent affair and could be fatal for people involved. It became an organised sport but eventually died out in modern Korea after the Japanese stopped the game in the eary 20th century.

Jeju Island was isolated from Korea and stone fighting would be detrimental to the already low population of the island. This meant that stone lifting was preferred by the locals. Not only was stone lifting used as a test of strength, but it united villages.

Jeju’s dol

Most villages on Jeju island had their own lifting stone. Villages with big stones were proud and prosperous because the stones were used as a measure of power. The larger the stone the more powerful the village. Having a larger stone — and more importantly the men able to lift it — implied a stronger, healthier, and more capable village. On the other hand, villages with smaller stones were ridiculed because it implied the villagers were weak.

Strangers entering other villages risked being challenged to lift the stone. Failing to lift the stone could mean a thrashing from the locals, and then the stranger was made to buy a round of drinks for trespassing.

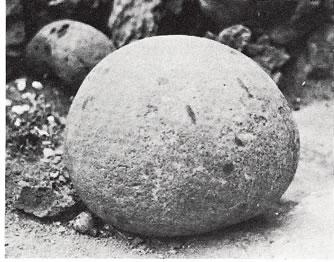

Most of the known lifting stones were rounded, smooth, and dense — weighing around 125kg. Remarkably similar to other traditional historic lifting stones. The Inver Stone immediately comes to mind when looking at an image of the Gosan village stone.

In the local dialect the stone is called ttum dol — literally lifting stone. Several known stones were embedded into walls in their villages with concrete, though it’s not obvious why.

Some of the island’s elders in the early 1980s recalled that the stones were used in contests of strength. These contests gave the simple answer to ‘Who is the strongest in the village?’. The last known stone-lifting competition on the island was around 1914 and the practice seemed to die-out after this.

Like other historic stone lifting cultures, Jeju island shares the practice of stone lifting as a rite of passage for young men as a test of their manhood. However we don’t know whether the lifting of the stone was as significant in meaning as it was in Scotland.

Origins

The origins of stone lifting on the island may be explained by a folk-tale described by David.

About 300 years ago the people of a village now called Daerim were advised by a p’ungsu “doctor” — a geomancer — that a dangerous weakness in landform existed to the west of their village. Alarmed villagers were instructed to reinforce that direction artificially, by lifting one gigantic stone upon another at the western border of the village.

Two massive stones were rolled into place, but no way could be found to stack them. Meanwhile, the village was in ambiguous peril. Miraculously, a young Mr. Pak from the village embraced one stone and singlehandedly lifted it upon the other. The village soon began to prosper, and was known for a time thereafter as Ipsok, “Standing-Stone” village. The village is now known by its Korean name of Sondol, which has the same meaning. Modern Daerim seems to be a fusion of the two once adjacent villages.

West of Ipsok, just beyond the stone pile, was the village of Suwon. As Ipsok prospered over the years, Suwon declined. The villagers of Suwon eventually placed the blame for their run of bad luck on the stone pile built by the Ipsok villagers to the east: the standing-stone had fouled the eastern border of Suwon, obstructing their fortune.

Suwon villagers dispatched a raiding party and toppled the perched stone. The villagers of Ipsok, who were now blessed with many strong young men, quickly replaced the fallen stone. The next day, however, it was down again. Then up. Then down. And so on for decades.

The parallels between this standing stone and the Saddlin’ Mare or the Puterach are immediately apparent — where the goal is to lift and place the stone on the plinth.

This legend may help explain the origins of the stone-lifting game in Daerim village, perhaps to commemorate the village feud, or to glorify the strength of young Mr. Pak. The custom may have spread from Daerim to other parts of the island. Daerim villagers identified the legendary standing-stone in the ‘down’ position in the photo above. Since no villagers can recall having seen the capstone in the ‘up’ position, it is presumed that this aspect of the Daerim-Suwon village rivalry petered out some time before the 20th century.

Losing a culture

Why then did Jeju lose the stone lifting culture that was practiced all across the island?

Clearing fieldstones was a seemingly endless job for peasants on the island. The nature of the volcanic environment meant that the land was full of stones that needed clearing to make space to grow crops.

Jeju men had a reason to confront the village stone at the end of a long day clearing fields. Lifting the village stone was a form of vengence after a day of wrestling with stones in the fields, and demonstrating victory over the ‘patriarch’ of the field stones was a way of proving the villager’s place in the natural order. Gathering to lift the stone was a demonstration of solidarity between villagers. It likely instilled confidence and boosted morale for the next day of work in the field.

Interest in stone lifting declined when focus of the peasants shifted from clearing fieldstones to plowing and processing crops. As the fertile land surrounding each village was claimed and cleared, the symbol of community spirit shifted away from the stone, and ‘towards the millwheel’ as it were. With fewer stones to clear, the fewer gatherings around the village stone were needed, until it eventually died out completely.

The stones exist as a legacy of back-breaking work, and the activity inspired by that work.

Lifting stones on modern Jeju

In the last 50 years or so, Scottish stone lifting has been revived and is more popular than ever amongst strength athletes. So what about the stones on Jeju Island? Could their stone lifting culture be rivived too? Do any of the stones still exist? Are locals aware of the culture the island once had?

I was confident that if any of the stone lifting culture on the island existed, that I’d be able to find some kind of reference to it. But my searching came up short. Nearly 40 years on from David’s paper, and there’s been no research or reference to the stones since.

Even before 1984, stone lifting was neglected on the island. Elders at the time remembered that the stones had once been lifted back in the 1910s. It’s likely that it has been over 100 years since someone intentionally lifted any of the stones.

If anyone knew anything about the stones now, it would be David Nemeth. So I contacted him, asking if he knew of any new information about the stones.

Unfortunately, he didn’t have any answers either. He did note that he ‘would have heard about it’ if anyone had started documenting, researching, or lifting the stones on the island. He was also ‘surprised that the tradition had not yet been exploited for profit or otherwise commodified by the huge tourism industry on the island’. Which yet again suggests that the tradition and culture of stone lifting is completely lost on the island.

David contacted friends of his on the island to enquire about the stones, and encouraged them to get into contact with me if they had any information to share regarding the stones. So far I haven’t heard anything.

As it stands, I’ve hit a bit of a dead-end. There has been no reference to the stones in decades, the island that relies heavily on tourism hasn’t exploited the culture in any way, and even the experts have seen no evidence of locals acknowledging their stone lifting heritage.

What’s next for the Jeju stones? I’m not giving up on trying to locate any of the stones and their stories. However, stone lifting hasn’t been practiced in over 100 years, so it’s unlikely there’s anyone with first-hand experience of the stones. The language barrier is a painful reality too. Unless I find someone interested enough to help research this ‘on the ground’, I fear I won’t find anything anytime soon.

Update: 26th October 2023

Jeju’s stonelifting culture is alive!

Richard Pretti has been researching Jeju’s stonelifting culture and has written an article about Jeju’s stonelifting legends along with new information on Jeju’s stonelifting culture.

Contributions

Special thanks to David Nemeth for his paper regarding the stones, and for his email correspondance. Several images and some of the text in this article is directly from David’s paper, which I have linked to below.

References

The Lifting Stones of Cheju Island, David Nemeth, 1984

Updated and revised essay (.pdf)

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.