The Ybrig Stone

Guest article by Daniel Kranzelbinder

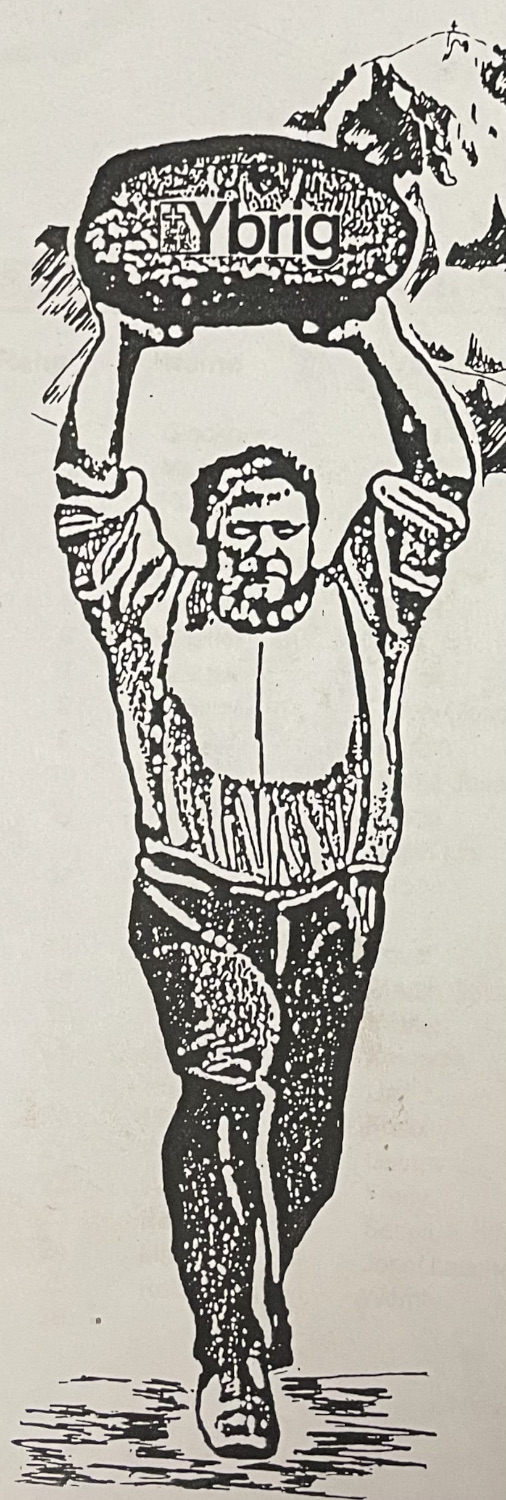

The Ybrig Stone – or Ybrigerstein – is the heaviest stone regularly thrown in Swiss stone putting competitions, weighing 90.5kg (200 lb). It’s easily identifiable by the engravings on its face: the name Ybrig, the coat of arms of the canton of Schwyz, and the year 1985.

Through its associations with the legends of the Ybrig Giant and the so-called Marchenstreit (boundary dispute), the Ybrig Stone represents a significant piece of cultural heritage for the Ybrig region. It’s also a symbol of strength, resilience, and the unconquerable spirit of Switzerland in general, and of the canton of Schwyz in particular.

The legend of the Ybrig Giant

The Ybrig Stone has roots in Switzerland’s Iberg region – Ybrig or Yberg in the local dialect – where legends tell of a giant named Hans Winz (or Vinz). While Hans Winz’s tales are mythical in tone and content, he’s sometimes considered a real historical figure.

One legend tells the story of Winz being visited by a fellow giant from Unterwalden who wanted to compete with him in feats of strength. Upon arriving, the Unterwaldener giant tied his horse to a large rock in front of Winz’s house, only for Winz to swiftly chastise him: that stone had fallen from the roof, where it was used as a weight, and was going to be moved back up!

The Unterwaldener giant protested that there was no need to move his horse, since the stone surely wouldn’t be put back anytime soon. In response, Winz grabbed the stone – said to be the size of a man – and threw it back up onto his roof. Having witnessed this, the giant of Unterwalden shook Winz’s hand and abandoned his plans for a strength contest. Other versions of the story have Winz lifting the horse several feet into the air.1

The most frequently told of Winz’s legends, however, records how the giant single-handedly held off an entire army at Ibergeregg Pass by throwing trees and enormous rocks at them.

We can appreciate the cultural significance of the Ybrig Giant’s legend when we understand the historic background against which it is set: the Einsiedeln army was launching a surprise attack on the people of Unteriberg as part of a centuries-long boundary dispute (the so-called Marchenstreit).

In the early 11th century, the Holy Roman Emperor Henry II granted the lands north of Grosser Mythen and Hoch‑Ybrig to the monastery of Einsiedeln, originating the territorial dispute between Einsiedeln and the rural community of Schwyz.

Winz’s legend of heroism in 1313 ties into one of the dispute’s violent flare-ups, beginning with the death of Albert I of Germany in 1308. In 1309, the abbot of Einsiedeln sought and obtained the excommunication of the people of Schwyz from the Bishop of Constance. Schwyz successfully appealed to the Pope in Avignon against their excommunication in 1310, but in 1313 they were excommunicated once again. The death of the Holy Roman Emperor Henry VII further aggravated the situation as now the House of Habsburg (protectors of the monastery of Einsiedeln) was preoccupied with consolidating its hegemonic ambitions elsewhere. Raids, pillaging and plundering resumed.

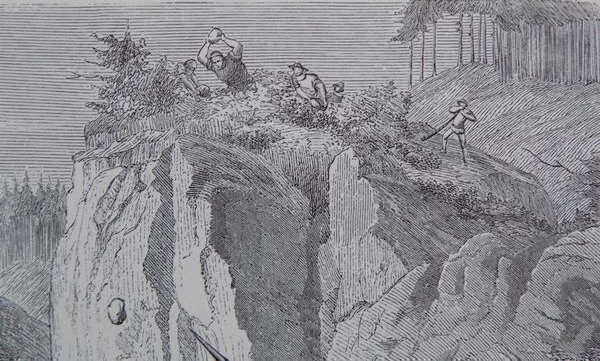

One version of Winz’s legend of 1313 says the raiding party from Einsiedeln launched a surprise attack on the people of Unteriberg, who had gathered in the central square for an assembly. Winz had departed late for the assembly and on his way over Ibergeregg Pass spotted that 300 armed men from Einsiedeln were approaching the unarmed and unsuspecting people of Unteriberg. Winz sent the boy who was with him ahead to warn the people while he himself posted up on the pass.

Winz knew that he wouldn’t prevail. His goal was merely to repel the approaching soldiers long enough to give the people of Schwyz time to prepare for the attack. Ripping fir trees and large rocks from the ground, Winz single-handedly held back the approaching army. Remarkably, the legend notes that the Ybrig Giant continued to hold off the raiding party on the mountain pass even after a man named Oechsli shot the giant in the chest with an arrow.

In a display of his unconquerable spirit (and a little dark humour) Winz is said to have turned to Oechsli with the words ‘Oechsli, you have made an exceedingly little hole in me [punning on the name ‘Oechsli’ and the word for ‘little hole’ (Loechli)] and yet I must die. But before I do, I’ll take you and many of your fellow men from Einsiedeln with me.’ Ripping trees from the ground to swat away the men who were now thronging him, the giant eventually succumbed to his injury.

With its connections to the Marchenstreit, the legend of Hans Winz ties into central elements in the foundation and liberation myths of the young Swiss Confederacy. The Marchenstreit’s destructive escalation is generally considered one of the reasons for the Federal Charter of 1291 from which the Old Swiss Confederacy emerged and a trigger for the Battle of Morgarten (1315) in which Schwyz defeated the army of Leopold I, Duke of Austria. The legends of Hans Winz are an expression of the pride the people of Schwyz take in their strength and resilience.

Hans Winz’s death was marked by a monument (no longer in existence) on the Ibergeregg mountain pass where the Ybrig Stone appears in the photograph below:2 3

The Revival of a Symbol

The legends of Hans Winz inspired local artist Bernhard Wagner: as far back as the 1960s his sketchbooks are filled with drawings of an Ybriger giant lifting up and throwing a massive rock to defend the people of his hometown from the raiders from Einsiedeln.

In the 1980s, Wagner’s preoccupation with strength, the mountains, towns, and traditions he grew up with led him to breathe new life into this enduring symbol. He accordingly commissioned a suitable natural stone to be retrieved in 1985 which was going to be the heaviest one thrown in competition: a stone worthy of the Ybrig Giant.

Josef Ambauen, at the time the dominant record holder with the Unspunnen Stone, was selected for this task. Ambauen scouted a stone in a riverbed, where it was retrieved and carried back to a stonemason’s workshop.

The stone was cleaned, smoothed, and engraved by Bruno Pfyl, whose name and workshop engravings are still visible on the top of the stone.

However, Wagner did not want to erase the stone’s natural form; this is why, to this day, the stone has a slightly lopsided shape, with the right-hand side jutting out further. The stone’s unusual, asymmetrical shape has confounded many an athlete and led to a variety of holds during both the cleaning and the pressing stages. While techniques vary, athletes generally prefer a two-handed overhead throw with run-up.

The Ybrig Stone, then, does not pretend to be an ancient stone, nor is it a replica or copy of an older stone (as in the case of its more famous brother, the Unspunnen Stone). It derives its meaning not from its function as a historical relic but from being a carefully curated tool to breathe new life into an old legend and to sustain the ancestral connection the people of Schwyz and of Ybrig have to their traditions, to strength, to self-sacrifice, and resilience.

From 1987 onwards, the Ybrig Stone was thrown in an annual festival in Oberiberg and guarded by Wagner. In recognition of its special role (and the significant athletic demands it places on those attempting to throw it competitively), it is now used only on special occasions; most recently at the Centennial Alpine Games of Schwyz in 2024.

While the Ybrig Stone’s ancestral location is on Ibergeregg Pass, Wagner initially kept the stone, and it has since been passed down for safekeeping to his godson, Bruno Ott. Those wishing to see the stone are encouraged to ask for him in the village of Unteriberg to seek permission and guidance.

Competitions and records

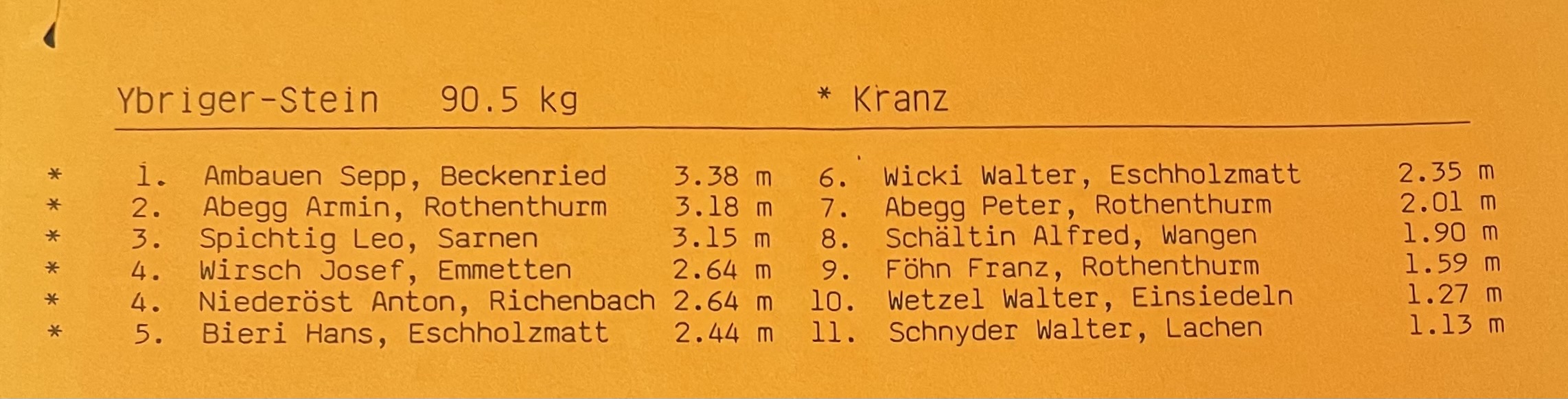

The first competition with the Ybrig Stone took place in 1985. Unsurprisingly given his dominant run with the 83.5 kg Unspunnen Stone, Josef (Sepp) Ambauen here also outdistanced his opponents:

The basic format and rules of the competition have been tightened considerably over the last forty years (as athletes have increasingly professionalised), starting with the 89th Alpine Games of Schwyz in 2012.

Unlike earlier competitions, there is a set number of attempts (two), a regulated run-up, and crucially, a regulated sandpit without a slope. Overstepping or stepping onto the beam/toe board is a foul. Martin Laimbacher was the first to win with a distance of 3.31m (10 feet, 10.31 inches) under these stricter regulations that govern competitions to this day.4

The current distance record under competition conditions was set at the Centennial Alpine Games of Schwyz in 2024 by Daniel Kranzelbinder with 3.55m (11 feet, 7.76 inches), narrowly beating serial winner of the Federal Alpine Games (ESAF) Remo Schuler’s 3.53m (11 feet, 6.98 inches) throw, and Unspunnen Stone record holder Urs Hutmacher’s 3.52m (11 feet, 6.58 inches) throw. The 2024 Centennial Alpine Games were the first competition ever where several athletes put the stone over 3.50m (11 feet, 5.8 inches).

Author

Daniel Kranzelbinder competes at the highest level in Swiss stone put. Over the last few years, he has reached the podium at the quarter-centennial Federal Alpine Games in Appenzell (2024) with the Unspunnen Stone, made the finals at the Federal Alpine Games in Glarus (2025) with the Unspunnen Stone, and won the Centennial Alpine Games of Schwyz with the Ybrig Stone in 2024. He teaches the history and philosophy of science at the University of Chicago.

Contributions

With many thanks to Bruno and Heidi Ott and their family for granting me permission to photograph the stone and for sharing with me their ancestors’ voice recordings and written accounts of the legends of Hans Winz. I am also grateful to Bernhard A. Wagner for agreeing to be interviewed and for making available his private archive and sketchbooks relating to the Ybrig Stone.

And with massive thanks to Daniel for sharing the full story of the Ybrig Stone.

Glossary

Marchenstreit – the long-standing conflict between the monastery of Einsiedeln, backed by imperial authority, and the rural community of Schwyz stemmed from Emperor Henry II’s transfer of lands north of the Grosser Mythen and Hoch-Ybrig mountains to the monastery. This conflict is widely seen as a key factor behind the Federal Charter of 1291, which laid the foundations of the Old Swiss Confederacy.

Federal Alpine Games (Eidgenössisches Schwing- und Älplerfest (ESAF)) – Switzerland’s largest traditional sports festival, held every three years. The festival is the largest event to feature the national sport of Steinstossen. First organised in 1895 in Biel, ESAF has grown into a major cultural celebration. The most recent edition in Mollis was the largest ever, drawing 56,000 spectators to the arena and 2.3 million TV viewers. The event preserves and promotes Swiss alpine traditions, attracting thousands of spectators who celebrate national identity through sport and folklore.

(Cantonal) Alpine Games – usually held annually, these traditional sports festivals feature disciplines such as stone put and Swiss wrestling (Schwingen). Athletes compete to win ‘wreaths’ and qualify for the Federal Alpine Games.

Kranz/Wreath (prize) – the Kranz is the most prestigious award in traditional Swiss sports. The word literally means “wreath” and refers to a crown made of woven oak leaves. Only the top-ranked athletes at a festival receive a Kranz. While historically common awards in Steinstossen, the sport has recently moved away from them.

References

Viertes Schulbuch für Primarschulen Zweiter Abschnitt. Kurze Beschreibung und Geschichte des Kantons Schwyz. Kanton Schwyz Einsiedeln, 1911

Steinegger (1981: 264). The painting and watercolour may follow the description of Winz’s house by Felix Donat Kyd von Brunnen (1793–1869)

-

Steinegger, Hans. (1979) Schwyzer Sagen Band I. Schwyz, Ingenbohl, Steinen, Morschach. Riedter Verlag, 267. ↩

-

Steinegger, Hans. (1981: 265ff) Schwyzer Sagen Band II. Muotathal, Riemenstalden, Illgau, Oberiberg, Unteriberg. Riedter Verlag. ↩

-

Dettling, Martin. (1860). Schwyzerische Chronik, oder, Denkwürdigkeiten des Kantons Schwyz. Gebr. Triner. Link: https://www.e-rara.ch/zuz/doi/10.3931/e-rara-22464, 17. ↩

-

https://steinstossen.ch/app/uploads/2025/08/1203-SZ-Kant-12.pdf ↩

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.