The legend of Ōiko’s stone

Milo of Croton’s legendary story of carrying a newborn calf every day until it grew into a fully-grown bull is so well known in the strength community that it’s often used to illustrate progressive overload. And while that’s a good interpretation, for me the tale’s lesson is the idea of consistency, daily progress, and incremental mastery beyond the context of strength.

Humanity has shared tales like Milo of Croton’s to pass down wisdom long before literacy and the invention of the printing press. And although the feats in some of these strength legends have been inflated through the generations, their underlying messages remain.

While legends like Milo’s bull resonate across cultures with their broad messages, others are deeply rooted in local traditions and values. For Shiga prefecture in Japan, an exceptionally strong woman from Takashima called Ōiko represents the second category. There are a couple of legends featuring Ōiko and her strength, but my favourite is related to her stone, a seven-foot-tall slab that she is said to have moved single-handedly during a dispute.

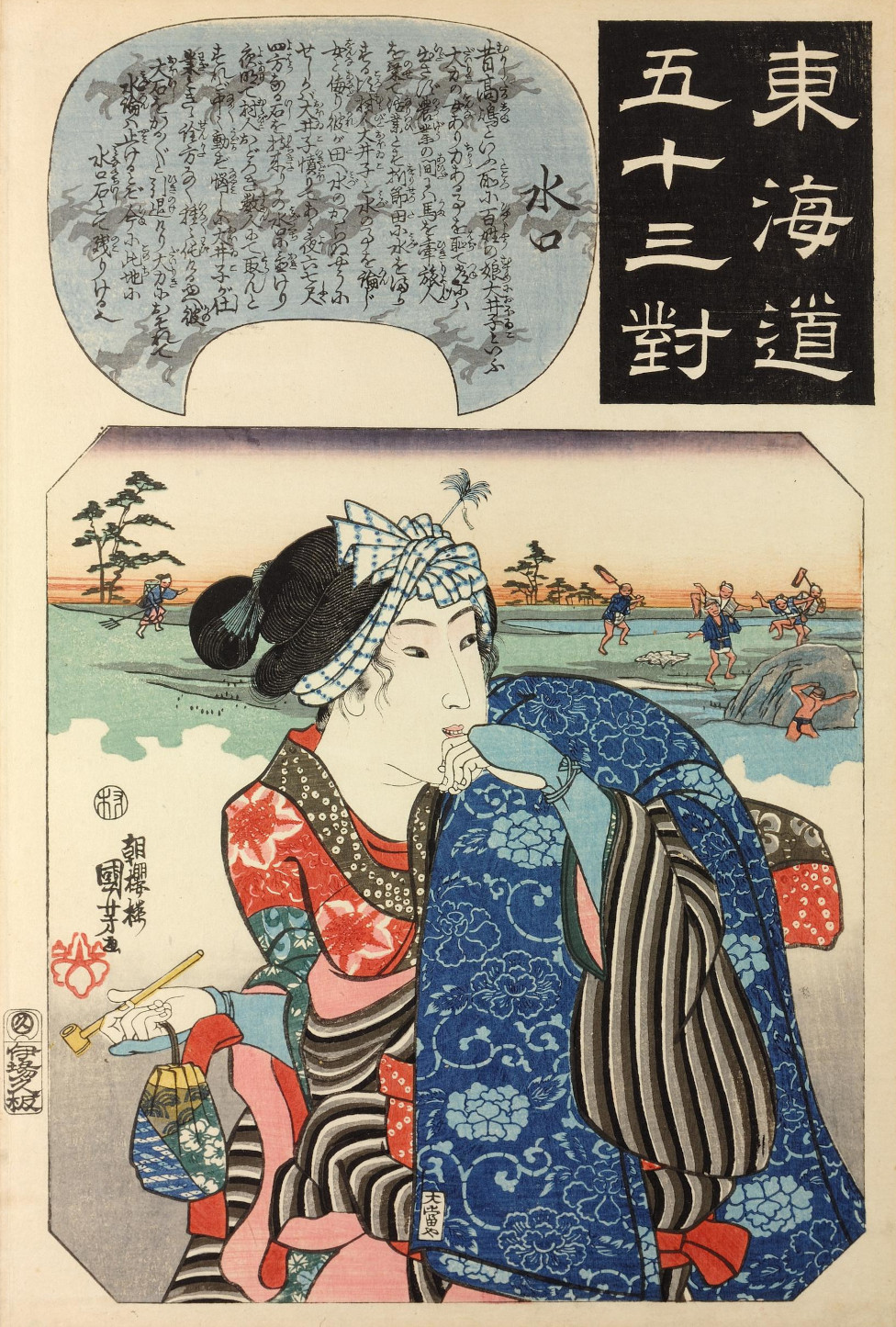

Ōiko’s feats were recorded in a Kamakura-period collection of tales called the Kokin Chomonjū1, compiled in 1254 by Tachibana Narisue. Although her dates of birth and death are unknown, the ordering of stories in the collection suggests Ōiko lived in the early 12th century. Her tales of strength have been retold for centuries and subsequently depicted in woodblock prints.

Ōiko wasn’t an all-powerful superhero-esque character, she was a rice farmer. Rice fields are notorious for their need to be flooded for the majority of the crops’ growth. And because the irrigations canals were (and still are) shared infrastructure, this need for water often triggered disputes over who could and couldn’t access it, especially during times where water was scarce. For a rice farmer, lack of water flow was a life-or-death situation – no water, no food. Ōiko’s stonelifting legend was born from this kind of water dispute. Here’s my own interpretation of the short tale.

The water dispute

Once upon a time, in a place called Takashima, there was a farmer’s daughter named Ōiko who was very strong. She was ashamed of her strength and rarely showed it off.

One day when the time came to distribute water into the village’s rice fields, the villagers argued over it. Eventually, the villagers came up with a plan to not allow water into Ōiko’s paddies.

That night, Ōiko went out and carried a stone about six or seven shaku across (6 to 7 feet, about 2 meters) and placed it at the water outlet, redirecting the flow from the others’ fields into hers. Water rushed into the paddies, flooding her crops as planned.

When dawn arrived, the villagers were stunned when they saw the stone redirecting the water. Several villagers tried to remove the stone, but none could budge it.

“If we try to drag the stone away, not even a hundred men could manage it. And even if we attempt it, we’d crush our fields. What are we going to do?”

The villagers begged and pleaded with Ōiko, “From now on we will let the water flow exactly as you wish, please just remove the stone!”

“I thought you would say that”, Ōiko replied.

Again, under the cover of night, Ōiko single-handedly moved the stone from the water outlet, allowing the water to flow freely into all the rice fields. The villagers never argued over water again.

This, then, was the first occasion on which Ōiko’s great strength was revealed. The stone in question, known as “Ōiko’s Water Inlet Stone” remains in that district to this day.

Ōiko’s power stone

That final line “The stone in question remains in that district today” instantly piqued my interest.

So I spent some time researching Ōiko and Takashima a little more, and it didn’t take long to find the monument displaying the stone that Ōiko used to settle the dispute. I thought that was going to be the end of that and stashed my research.

A few months later, I found myself walking round Kyoto a little tired from visiting all the tourist sites when I saw a library. I impulsively walked in to take a look. I didn’t have high hopes, but maybe I’d find some information on Japan’s power stones?

I approached a library computer and typed in 力石 – chikaraishi, Power Stone or Stone of Strength – to search for any information. To my surprise, there was a result! I took a photo of the screen to note the book’s location.

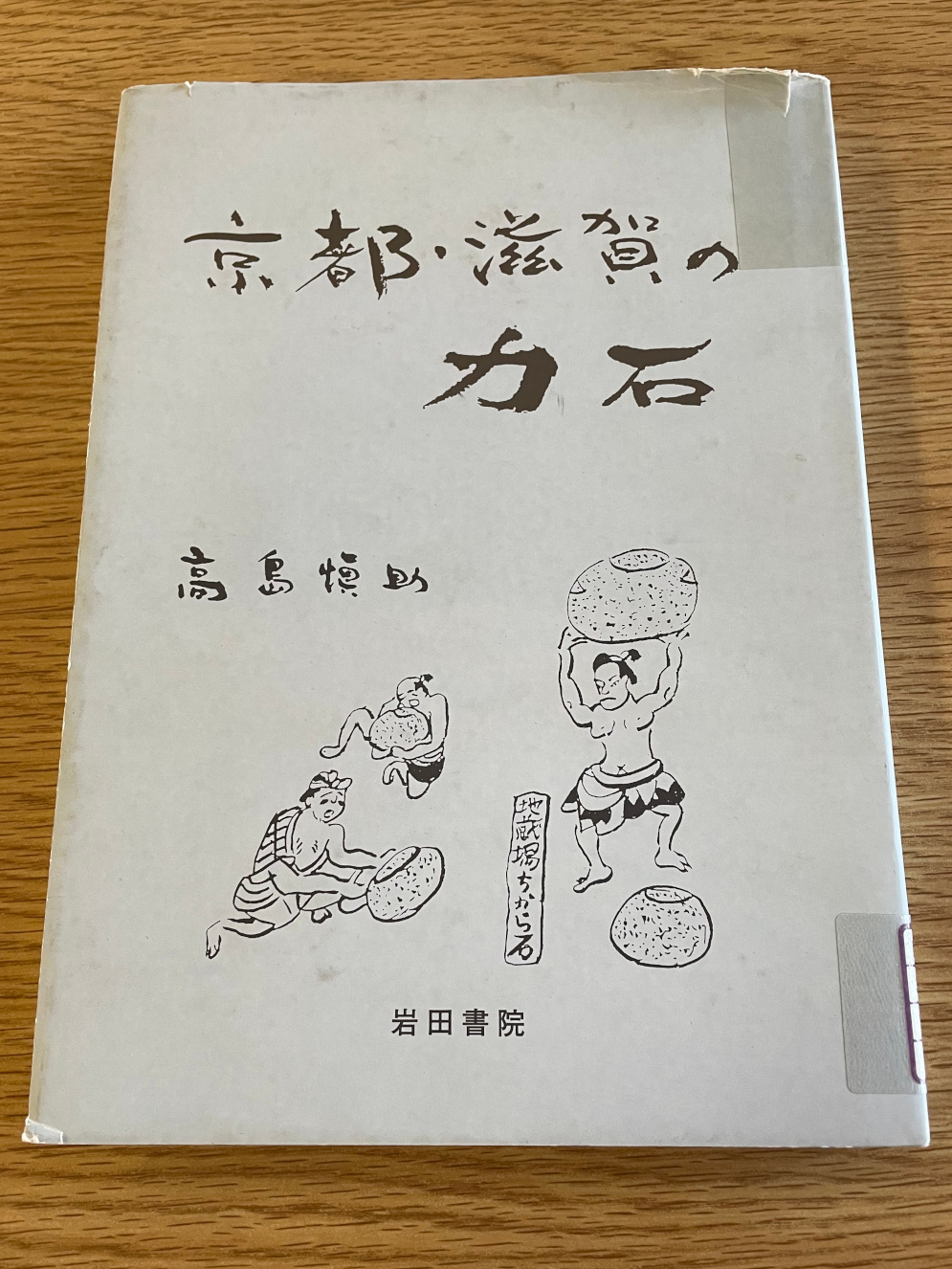

After a bit of searching on the shelves I found it: Kyoto and Shiga’s Power Stones by Takashima Shinsuke, Japan’s foremost power stone researcher.

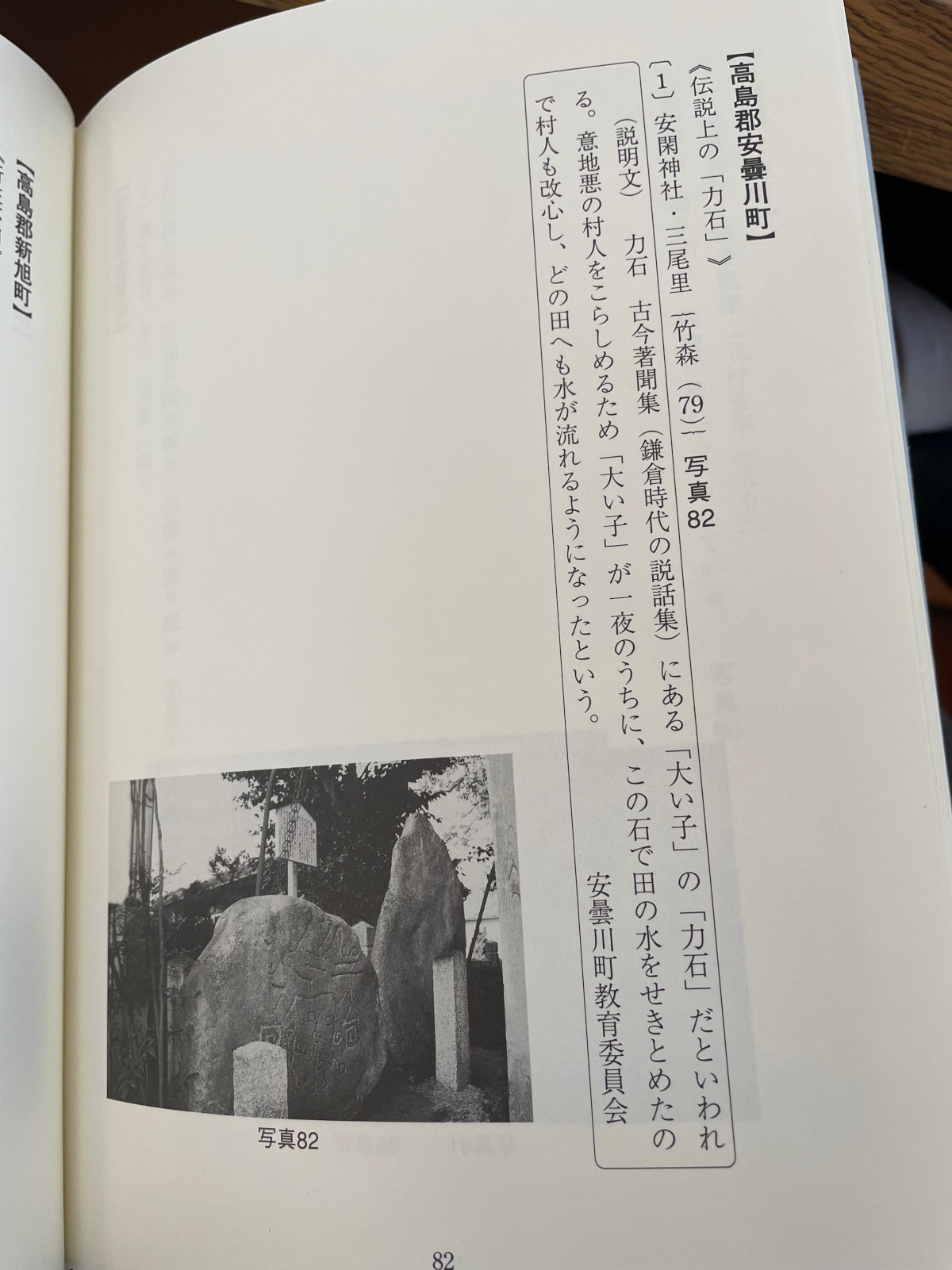

I sat down and flicked through the book looking for some interesting stones that I might be able to visit. When I reached one of the final pages, I found a familiar-looking slab along with a brief outline of the water dispute story.

I took a photo of the page (and a few more) to stash away as research, but I didn’t intend to visit Ōiko’s power stone.

A few days after finding the book, I woke up with no plans and no idea what to do. I pulled out my phone and tapped on the map app to look for inspiration. As soon as the map loaded, the first place label I saw was Takashima. It was probably just a coincidence, but something was drawing me to Ōiko’s home town and her stone.

Without overthinking it, I grabbed my bag and caught the next train heading north-east.

It’s interesting how Japan changes the farther you get from the big cities and popular tourist spots. Through the train window, instead of an ocean of people, I watched blankets of rice paddies roll by. Then, when I got off the train at Adogawa station, a perfectly-uniformed man checked my ticket by hand instead of the automated gates I was used to in the city. But the biggest difference was the quiet – no traffic, no crowds.

One of the downsides of modern technology is that you rarely need to ask locals for directions. I usually try to chat with locals since they often know details you won’t find online, especially around local lore and historic stones. But the streets were empty, so I pulled up the stone’s location on my phone and strolled through the town.

Adogawa’s streets were lined with rice paddies and irrigation canals feeding water to them. The crop was still young; it had only been planted a few weeks before I arrived.

By coincidence, I was visiting the stone at roughly the same time of year Ōiko’s legend took place. And that timing made it easy to imagine her from those woodblock print scenes in this town nearly a thousand years ago.

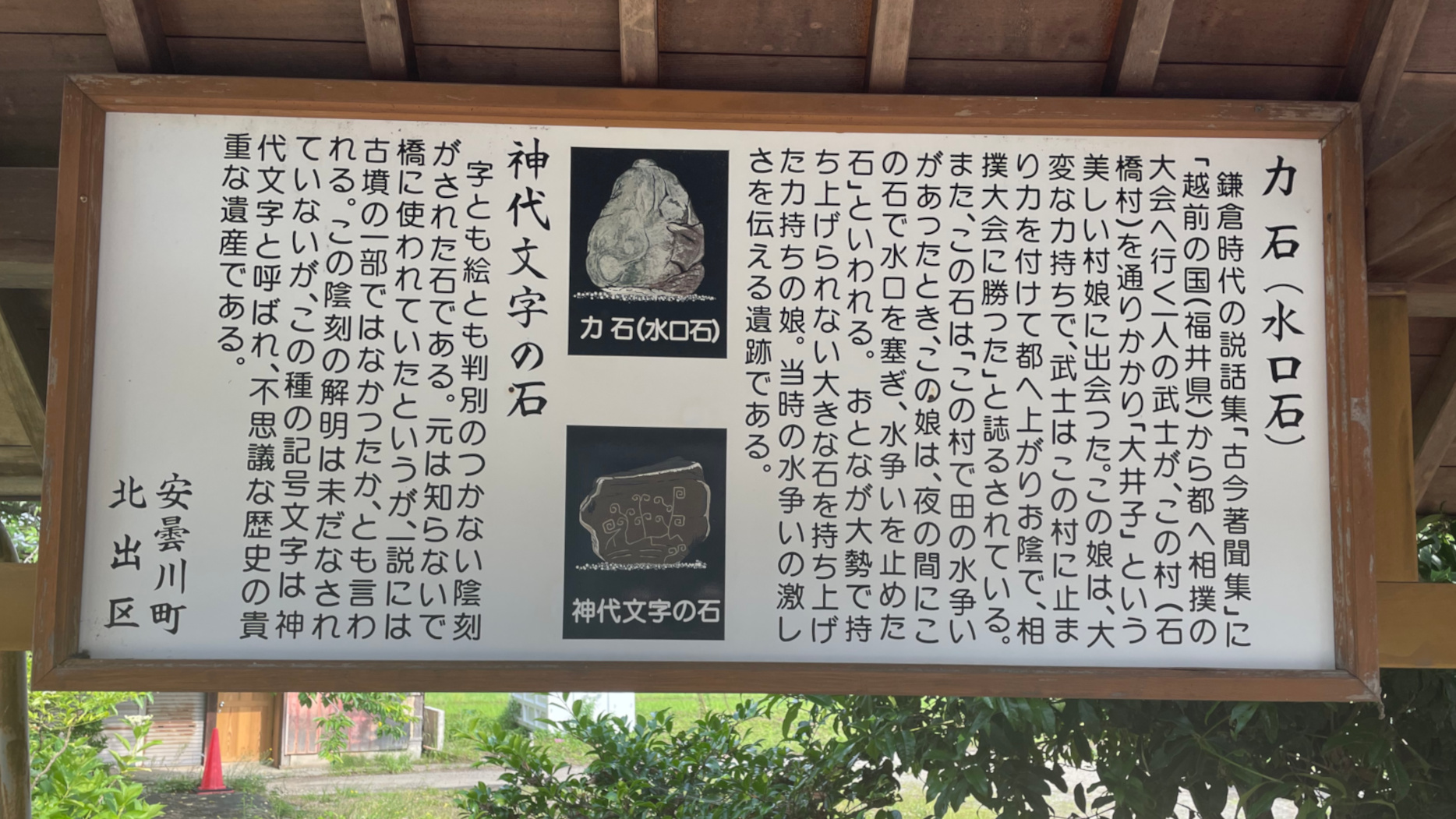

Turning a corner into a residential-looking area, I saw the stone display right in the middle of a small courtyard.

I couldn’t ask any locals about the stone, but I do know it’s been on display for a while – over 20 years based on the publication date of the Kyoto and Shiga Power Stones book, and possibly far longer.

While the stone is tall and wide, it’s relatively thin – maybe 8 inches (20 cm) at its thickest points. And it roughly matches the description from the legend: 6 to 7 shaku (6-7 feet, about 2 meters) across, give or take. Although in this orientation, that would be the stone’s height.

Comparing it to Japan’s heaviest power stone from earlier in my trip, Ōiko’s stone looked taller and wider, but much thinner. I’m not great at estimating weights of stones, especially massive ones like this, but I’d guess it’s between 500kg and 600kg (1,102 lb - 1,323 lb).

When faced with tales of someone lifting such an enormous stone, it’s easy to be sceptical. And that’s fair – but it misses the point. Part of the reason legends like these endure for millennia is precisely because they push the boundaries of what we believe is possible.

Ultimately, the stone stands as a symbol of Ōiko and her legendary strength, while the quiet rice fields surrounding it reflect the lessons learned through her story. Together, they reinforce the deep-rooted Japanese concept of wa – group cohesion and collective well-being – even during life-or-death resource disputes.

Alongside the wisdom, the imagery of a folk hero like Ōiko lifting a massive stone simply excites and inspires people, like Strongman competitors do today. I don’t think it’s a stretch to say that some of Japan’s historic power stones exist because Ōiko and her story motivated people to prove their strength.

I challenge any stonelifter to stand in the shadow of Ōiko’s stone, surrounded by the rice fields, and leave without feeling hungry for both a second helping of rice and a heavier stone to lift.

Location

Ōiko’s power stone is located in Adogawa, Takashima City, and is easily accessible just a short walk from Adogawa train station.

The location is on the liftingstones.org map.

Ōiko and the sumo wrestler

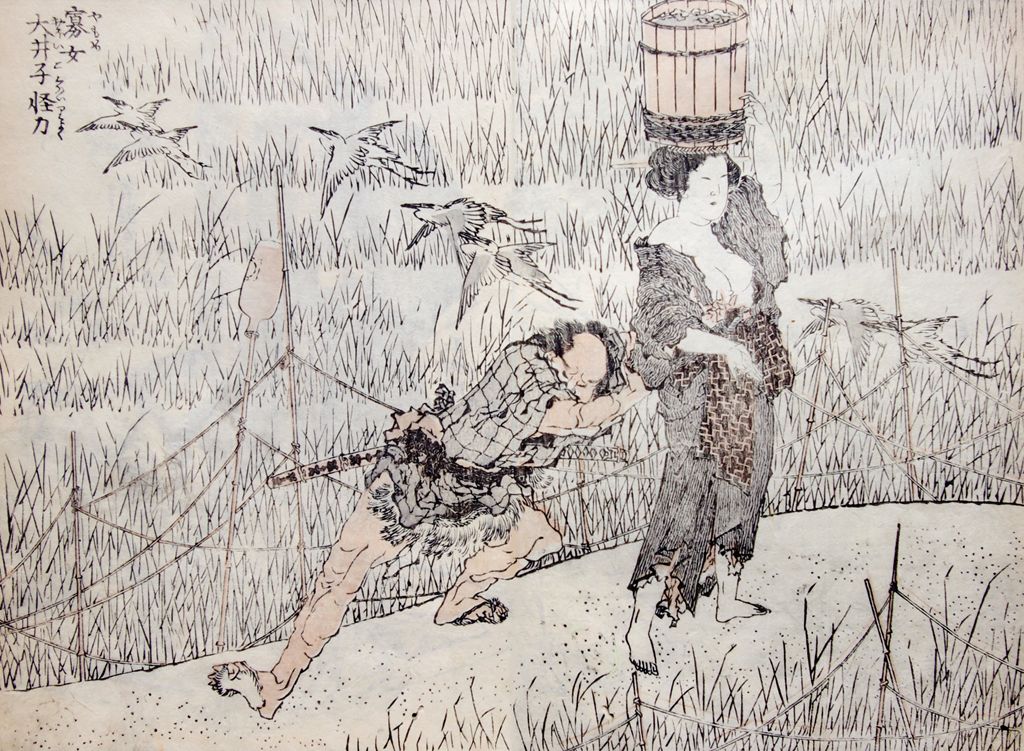

The first tale from Kokin Chomonjū tells of Ōiko’s encounter with Saeki Ujinaga, a man famous for his strength. And it’s this tale from which Ōiko was first depicted in print performing a feat of strength by the legendary artist Katsushika Hokusai – best known for The Great Wave off Kanagawa – in Volume 9 of Hokusai’s Manga.

The following is my interpretation of the first story – it’s not related to stonelifting, but it gives more of a view of Ōiko and her personality. It feels like a shame not to recount it.

An imperial sumo tournament was to take place in Kyoto, Japan’s capital city at the time, where strong men from all provinces were summoned to take part. Saeki Ujinaga from Echizen Province (modern Fukui) was one of those strong men competing.

While travelling to Kyoto, Saeki Ujinana was passing through Takashima when he came across a beautiful woman carrying a bucket of water on her head – of course, this woman was Ōiko.

Ujinaga was so struck with Ōiko’s beauty that he dismounted his horse and reached out to grab her. Unphased, Ōiko laughed and clamped down on Ujinaga’s arm, pinning it tight under her armpit. She grasped so tightly it made him wince in pain. She continued calmly walking with the bucket of water on her head and the strong man in tow. Despite trying to pull away with all his strength, Ujinaga’s hand was trapped. Ōiko easily overpowered him.

Full of shame, Ujinaga was led back to Ōiko’s home. When they arrived, Ōiko released Ujinaga from her grasp. Laughing, she asked “By the way, who are you, and why are you doing such a thing?”

“I’m Saeki Ujinaga, I’m travelling from Echizen to compete in the sumo tournament.”

Ōiko nodded. “That is dangerous business. The imperial palace is vast, and men of extraordinary strength will gather there. You’re not a weakling, but you are not ready for such a difficult contest. There is still time before the tournament, stay here for three weeks – I will feed you and help you gain strength.” Ujinaga accepted.

That night, Ōiko began feeding him large portions of firm rice balls called kowameshi – literally strong rice. At first, he could not bite through the balls of rice she made. During the first week, he struggled to break through them at all. After another week, he managed to bite into them. On his final days with Ōiko, he could easily chew through the rice.

“Now, proceed to the capital. In this condition, you should perform just fine” Ōiko said, sending Ujinaga on his way.

It’s said that Saeki Ujinaga performed well in the tournament.

Notes

Both the water dispute and sumo wrestler legends are interpretations of the Kokin Chomonjū text.

Utagawa Kuniyoshi portrayed Ōiko multiple times in different print series, including ‘Biographies of Wise Women and Virtuous Wives’ (1842), ‘Fifty-three Pairings for the Tōkaidō Road’ (1845-1846), and ‘The Sixty-nine Stations of the Kisokaidō’ (1852). Interestingly, Utagawa Kuniyoshi depicted her at locations like Iwamurada and Minakuchi that weren’t her hometown of Takashima, suggesting he was drawn to her story rather than connecting her to a particular place.

Takashima Shinsuke, in his book Kyoto and Shiga’s Power Stones, lists Ōiko’s stone as 伝説上 (densetsujou, legendary)2, supporting the idea that it’s likely more a symbol than a historic artifact.

Glossary

chikaraishi (力石) – Traditional Japanese “power stones” or “stones of strength” used to test strength throughout Japan.

densetsujou (伝説上) – Literally “legendary” or “mythical”. Used to classify historical artifacts that are based in legend rather than verified historical fact.

Kokin Chomonjū (古今著聞集) – A collection of tales compiled in 1254 by Tachibana Narisue during the Kamakura period, containing some of the earliest written accounts of Ōiko’s feats.

kowameshi (強飯) – A type of glutinous rice dish, literally meaning “strong/firm rice”, an ancestor of today’s okowa (おこわ). In the Sumo wrestler story, Ōiko packs kowameshi into rock-hard rice balls that the wrestler must learn to bite through as part of his training.

minakuchiishi (水口石)3 – Literally “water inlet stone”. In Ōiko’s legend, the term refers to the massive stone she moved to redirect water flow. Both chikaraishi and minakuchiishi are used interchangably when referring to Ōiko’s stone.

Ōiko (大井子 / 大井児 / 大い子 / おほゐこ) – The name of the legendary strong woman (pronounced “Oh-ee-ko”, with a long ‘O’), written in different ways throughout historical texts.

shaku (尺) – A traditional Japanese unit of measurement equal to approximately 30.3 cm or 1 foot. Used in the story to describe the size of Ōiko’s stone.

wa (和) – The Japanese concept of group harmony and collective well-being, emphasized in the moral of Ōiko’s water dispute story.

References

British Museum. “Woodblock print by Utagawa Kuniyoshi from ‘Biographies of Wise Women and Virtuous Wives’” © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_2008-3037-15615

British Museum. “Minakuchi Station. The strong woman Oiko watches peasants marvelling at the great rock that she moved single-handed.” © The Trustees of the British Museum. Shared under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) licence. https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/A_2008-3037-04354

-

Yatanavi. Kokin Chomonjū, Chapter 15: Sumo and Feats of Strength, Tale 377: When Saeki Ujinaga First Traveled from Echizen Province for the Sumo Tournament. Digital text archive. https://yatanavi.org/text/chomonju/s_chomonju377 ↩

-

高島慎助, 京都・滋賀の力石 Takashima Shinsuke, Kyoto and Shiga’s Power Stones, 2004, page 82. ↩

-

National Folklore & Yokai Database reading for 水口石: https://www.nichibun.ac.jp/cgi-bin/YoukaiDB3/youkai_card.cgi?ID=3880058 ↩

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.