Hida Folk Village’s lifting stones

Unless you’re especially lucky, it’s difficult to imagine being a knowledgable stonelifter and accidentally stumbling upon historic stones you didn’t know of in places like Scotland and Iceland. That’s not really the case in Japan as I discovered on my trip back in 2023.

In fact, I actually ran into some historic stones of strength a few times. The first time was at Tomioka Hachiman Shrine (a shrine closely associated with sumo) in Tokyo. While making my way to the Kokugikan for the Grand Sumo tournament, I visited the shrine to see the Yokozuna memorial, where the names of every Yokozuna in Grand Sumo history are carved in stone. As I explored the shrine’s grounds to look at the other monuments, I saw seven stones proudly displayed at the chikaramochi (strongman) monument.

Just a few days later, I came across another group of stones at Oyama Shrine in Kanazawa. These were mounted like the stones in Tokyo, making them unliftable. Even so, it was still incredibly exciting to find them and touch them for good health.

One of the reasons you can encounter stones like this in Japan is that there are over 15,000 known chikaraishi (power stones). As a consequence, discovering these stones at shrines – and sometimes just walking straight past them, as I found I’d done after my visit to Sensō-ji1 – isn’t uncommon.

By now, I started wondering whether I’d strolled past any other stones, or rather, just how many had I narrowly missed? And wouldn’t it be cool to discover hidden liftable stones I hadn’t already planned to visit?

That evening when I returned to my hotel, I opened Instagram for the first time in a few days. The very first thing I saw was a Canadian tourist lifting a pair of power stones. That was cool in itself, since it’s rare to see. Interestingly, they also highlighted how they had no idea the stones were there, proving that when you keep your eyes peeled, you can spot them all over.

The Instagram post was tagged with a location, and I immediately checked to see where the stones were: Hida Folk Village, an open-air museum on the outskirts of the historic town of Takayama in the Japanese Alps. My eyes lit up!

In one of the biggest coincidences of my life, I already had a trip to Takayama planned for the very next day! The train tickets were already in my pocket. I knew of Hida Folk Village, but I hadn’t planned to go. But now that I knew there were stones, I’d made up my mind.

I had to wake up pretty early the next morning to catch my train. Normally, I’d be half-asleep, but the excitement of finding the stones had me ready to go. Getting to ride on one of Japan’s famous scenic trains didn’t hurt either.

I enjoy reading on trains when I’m traveling. As much as its nice to stare out the window, it can get boring on journeys lasting hours. Riding through the Hida mountains though, my book became about as interesting as the paper it’s printed on. They don’t call it a sight-seeing train for no reason.

While I didn’t want the train ride to end, we eventually arrived at Takayama. Crowds of people headed toward the historic district to see its famous wooden buildings, but I skipped the crowd and bought a ticket for the next bus to Hida Folk Village.

The bus ride wasn’t long – you could easily walk to the museum if you had time – but my impatience got the better of me. And unlike the train, the bus felt like it was crawling. When it finally arrived I hurried off the bus, powered straight to the entrance, handed over my ticket, and stepped through the gate.

The museum greeted me with a serene view of the pond and the house overlooking it. That calm in the morning sun next to the pond was a reminder to slow down a little – the stones weren’t going anywhere.

One of the first things I learned about Hida Folk Village is that it’s actually a man-made creation. The current village opened in 1971 with mutiple historic buildings that were relocated for preservation as an open-air museum2. Some of these structures were relocated from Shirakawa-go, another popular tourist destination in the Hida region for those interested in Japan’s heritage.

Part of the reason these historic buildings are so iconic is thanks to their high-ridged thatched roofs. Apart from just being aesthetic, these buildings are perfect expressions of form from function: the Japanese Alps are notorious for heavy snowfall during the winter, and the steep angles of the roof allow heavy snow to slide off easily, stopping the structure from collapsing under the weight.

As much as I was captivated by the museum, I still had the stones on my mind. I made sure to walk along every path, look behind every building, and search around every tree I could find. But still no sign of them.

Most mornings, the museum staff light the irori sunken hearths in the buildings. One reason they do this is for preservation of the buildings – the fires dry the buildings from within. Lighting the hearths also makes the buildings look as if they’re being lived in. Combined with seasonal events like planting rice, the village feels alive.

After covering at least three quarters of the site, I started to worry I’d missed the stones altogether. But as I walked down the steps from the shrine towards the torii gate, I noticed a sign post nestled between some trees with two egg-shaped stones hiding in the grass. I found them!

Without the sign post marking their location, I doubt anyone would ever notice the stones sitting there as anything out of the ordinary.

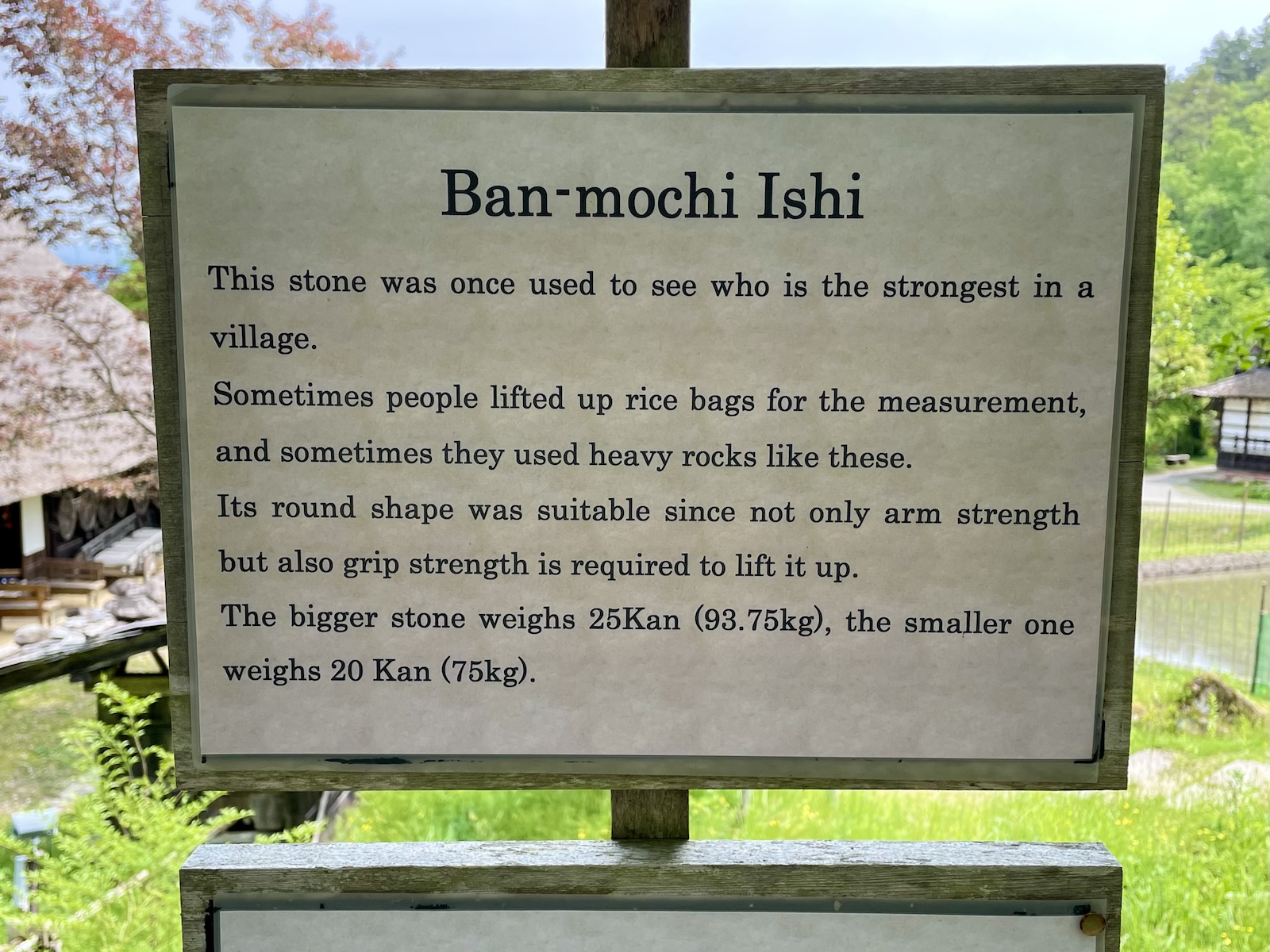

These stones are labeled as banmochiishi. There are various names for power stones across Japan, some names refer to how the stone is supposed to be lifted, while others – like banmochiishi – seem to be regional names for power stone. Regardless of their label, the purpose of the stones is clear: see who is the strongest in the village.

Like most Japanese lifting stones, these stones are measured in kan, an old unit equivalent to 3.75kg (8.267 lb). The smaller stone weighs 20 kan (75kg, 165 lb), while the heavier of the pair weighs 25 kan (93.75kg, 207 lb). Unlike many power stones in Japan, these haven’t been engraved, however, their rounded shape and smooth surface make them easily recognizable as lifting stones. But where did they come from?

The sad part is that I haven’t been able to find any information about the Hida Folk Village lifting stones – no stories, no legends, barely a mention anywhere. I know of some lifts, but they were all fairly recent, so I can’t even guess how long they’ve been here.

Were these stones here when the museum opened in 1971? Or were they sourced and placed by the museum to help illustrate elements of rural life?

Were they moved alongside one of the buildings for preservation? Or did workers find the stones when putting a building in place?

Disappointingly, I can only speculate – I have no answers.

Standing over the stone, one can imagine life in this fictional village: planting rice, visiting the shrine to wish for a good harvest, then lifting stones with friends before gathering around the family hearth for dinner.

And if you let the village immerse you, something magic happens. As you break the stone from the floor, bring it to your lap, and raise it to your shoulder, you feel as though you’ve stepped back in time – to a time where daily life was grounded in physical labour to feed one’s family and stay warm through the long winters.

Regardless of these stones’ history, they brilliantly illustrate how stonelifting may have fit into rural Japanese life.

The bus back to Takayama was arriving soon and there wasn’t much left for me to see in the village. The stones really were in the last place I looked. So I enjoyed some more views of the Hida mountains to pass the time.

On the walk back to the bus stop, I glanced at the museum’s site map only to discover that if I took a second to study it before rushing in, I would have seen the stones’ location nicely illustrated.

Had I not stumbled upon the stones scrolling online, I may not have discovered them – or Hida Folk Village – at all. I’m thankful my itinerary allowed me to wander; I’ve found the unplanned parts of travel are often the most memorable. And I didn’t know it at the time, but this wouldn’t be the last spontaneous lifting stone discovery of my trip.

Location

The Hida Folk Village stones are located at Hida Folk Village, an open-air museum a short bus ride from Takayama train station. Entry to the museum costs around ¥700, or you can get a combination ticket for the return bus journey from the station along with museum entry for around ¥1,000.

The stones sit on the west side of the site near Yoshizane’s house. I’d recommend exploring the museum as intended first for the full experience, however.

Their exact location is on the liftingstones.org map.

Glossary

yokozuna (横綱) – The highest rank in Grand Sumo, often translated as “Grand Champion”.

chikaramochi (力持ち) – Strongman, strong person.

chikaraishi (力石) – Traditional Japanese “power stones” or “stones of strength” used to test strength throughout Japan.

hida no sato (飛騨の里) – Hida Folk Village.

banmochiishi (番持ち石) – Another term for a power stone or stone of strength.

irori (囲炉裏) – A traditional Japanese charcoal-fired sunken hearth.

kan (貫) – A unit of measurement approximately equivalent to 3.75kg (8.267 lb).

Notes

-

In my defence I was in Asakusa during the Sanja Matsuri (one of the largest Shinto festivals in the whole of Japan), so it was close to impossible to move, let alone discover some stones tucked away in a corner of the Sensō-ji area. ↩

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.