Are you stronger than a sumo wrestler?

Every November, hundreds of sumo wrestlers descend upon the city of Fukuoka for the final Grand Sumo Tournament of the year, which the city has held since 1957.

Fukuoka’s sumo heritage stretches much further back than the mid-20th century thanks to Kushida Shrine — an ancient shrine in the heart of the city.

Kushida Shrine is said to have been built around the year 757, meaning it’s over 1,250 years old! And in the shrine’s long history, it’s been the centre of cultural events — most notably the 700-year-old Hakata Gion Yamakasa festival held annually. But Kushida Shrine also hosted sumo wrestling matches.

Kushida Shrine’s power stones

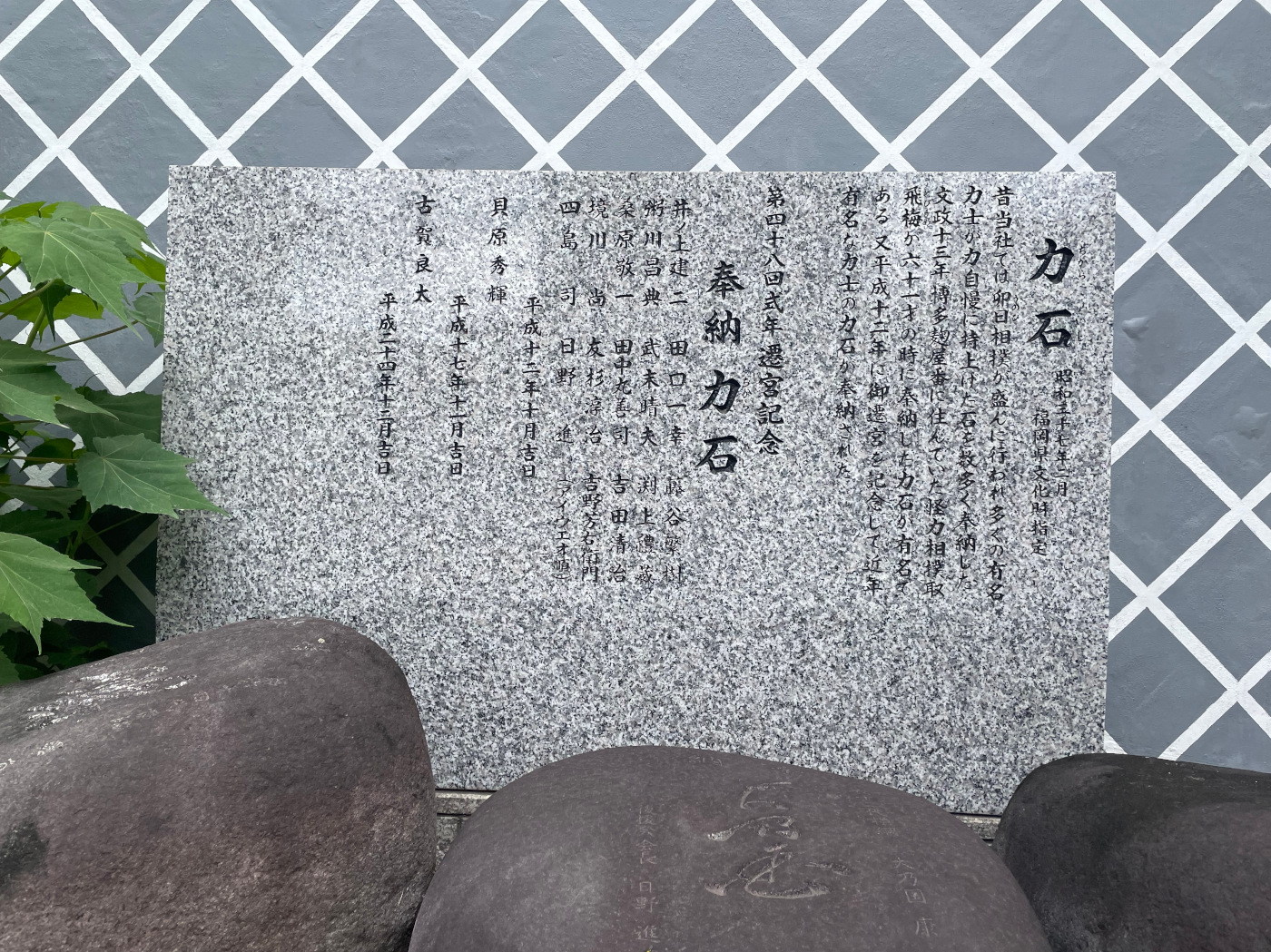

Kushida Shrine no longer hosts sumo matches, but it does have some incredible artifacts to commemorate its sumo history — a group of 力石 chikaraishi power stones dedicated by various sumo wrestlers over nearly 200 years!

However, sumo wrestlers haven’t dedicated all the stones at Kushida Shrine. One stone was dedicated in 1830 by Tomita Kyuemon, whose name appears on a stone weighing 172.5kg (380lb). Tomita was a supplier of somen noodles for the Fukuoka domain and the great-grandfather of the painter Tomita Keisen.1

On two other stones, among the engraved names are those of two known ship merchants: Ishuya Isuke and Urushima Isuke.1 Fukuoka is a port town, so many power stones in the city are thought to have been dedicated as prayers for safety in the waters or to wish for an abundant catch!

The first sumo wrestler to lift a stone at Kushida Shrine was 飛梅 Tobiume (Lit. Flying Plum) in 1830. Tobiume was described as having “superhuman strength”, and he demonstrated it by lifting a heavy stone, dedicating it to the shrine’s Kami when he was 61 years old! Tobiume’s feat started a custom for strong sumo wrestlers to dedicate stones to the shrine.

Each stone carries engravings of the wrestler’s ring name, rank, and other details.

There’s a large range in the stones’ weights. The smallest stone on display weighs around 80kg (176 lb), while others weigh upwards of 150kg (331 lb) and 172.5kg (380 lb). The most recently dedicated stones weigh around 120kg-130kg (265 lb - 287 lb).

The following wrestlers all have stones dedicated at Kushida Shrine:

- Tobiume, 1830

- Futabayama — 35th Yokozuna

- Wakanohana Kanki — 45th Yokozuna, Uncle to the Takanohana and Wakanohana brothers.

- Asashio — 46th Yokozuna

- Sadanoyama — 50th Yokozuna

- Kotozakura — 53rd Yokozuna

- Chiyonofuji — 58th Yokozuna

- Kirishima — Ōzeki from Kagoshima prefecture

- Onokuni — 62nd Yokozuna

- Akebono — 64th Yokozuna, first foreign-born Yokozuna

- Takanohana — 65th Yokozuna

- Wakanohana Masaru — 66th Yokozuna

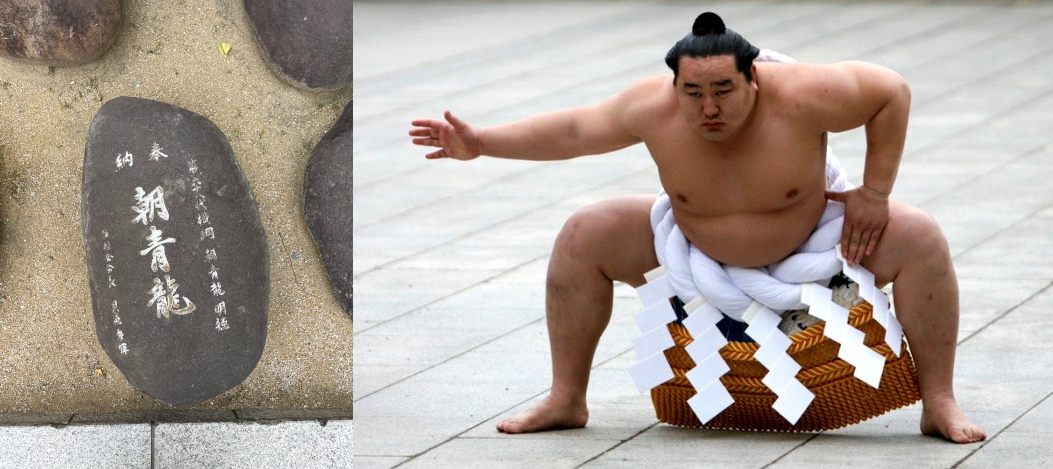

- Asashōryū — 68th Yokozuna

- Hakuhō, 2012 — 69th Yokozuna

Among these wrestlers are many of the sport’s greats — the “dai-yokozuna” or Great Yokozuna — men who not only reached the highest rank in the sport but who went further and dominated during their era, shaping sumo.

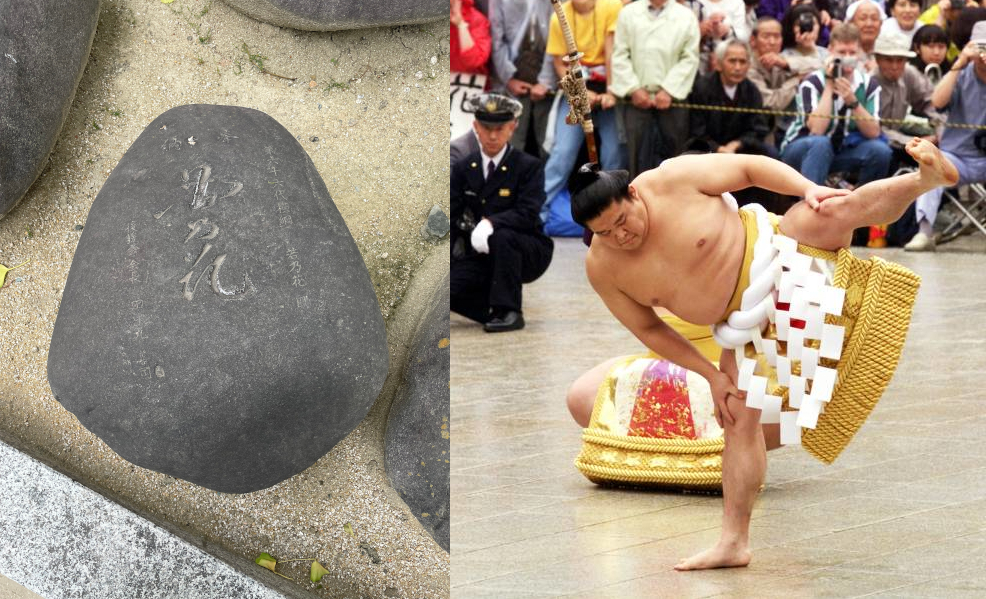

Chiyonofuji

Known as The Wolf, Chiyonofuji is one of history’s most well-loved sumo wrestlers. He’s also one of the most successful.

Chiyonofuji’s lean physique, athletic fighting style, and unmatched spirit earned him thirty-one championships (third most in history) and a generation of fans.

For eight consecutive years in the 80s, Chiyonofuji took the championship in Fukuoka, winning in the city a total of nine times.

Chiyonofuji probably didn’t consider Fukuoka his lucky city, though. On the final day of the 1988 Fukuoka tournament, Chiyonofuji’s streak of 53 consecutive wins was squashed by Onokuni, another Yokozuna with a stone at Kushida Shrine.

Chiyonofuji’s stone is difficult to read because dark blotches mask the finer engravings. Other stones on display don’t have this problem. Could it be that Chiyonofuji’s fans touch the stone for a connection to the late, great Yokozuna?

Takanohana, Wakanohana, and Akebono

A sentence on the sign reads:

又平成12年には御遷宮を記念して近年有名な力士の力石が奉納された。

Translated:

Additionally, in 2000, in commemoration of Sengu, recently famous sumo wrestlers dedicated power stones.

While not explicitly named, these wrestlers were likely the famous “Waka Taka Brothers”, Wakanohana and Takanohana, along with the first foreign-born Yokozuna, Akebono.

The brothers became the faces of sumo in the 90s when they both reached the highest rank of Yokozuna.

Each brother has their own stone dedicated at the shrine. Their Uncle, also with the ring name of Wakanohana, has his own stone too!

The brothers’ popularity was so great that the number of new recruits in sumo exploded, and the number of wrestlers in professional sumo peaked. As a result, their era of sumo is often referred to as the “Waka Taka Boom”.

Although both brothers reached the highest rank of Yokozuna, Takanohana — the younger of the two — was far more successful. Takanohana became the youngest ever wrestler to win a top-division championship at 19 years old, and he went on to win twenty-two championships compared to Wakanohana’s five.

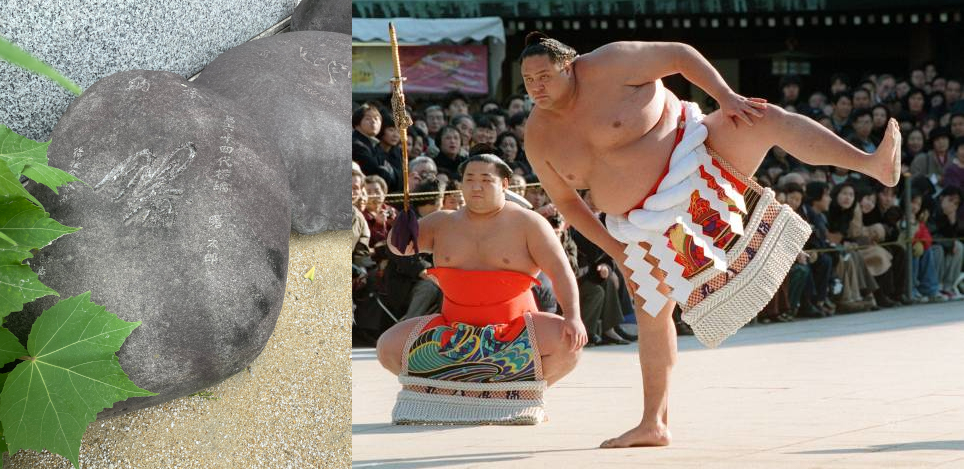

The brothers weren’t the only Yokozuna at the time. The 90s saw the first foreign-born man promoted to the sumo’s top rank in Akebono, a giant from Hawai’i standing at 203cm (6 feet 8 inches), 233kg (514 lb).

Akebono’s historic promotion wasn’t just an athletic achievement — it was a cultural one. Yokozuna are expected to embody Japanese values like hard work, humility, and strength. But Yokozuna are also expected to possess 品格 hinkaku, a uniquely Japanese style of dignity, grace, and character.

Brothers (and stablemates) never fight each other in tournament bouts, so Wakanohana and Takanohana never clashed except in playoff matches. This left Akebono as the primary rival of the brothers in the ring, especially Takanohana.

After 50 total bouts throughout their rivalry, Akebono and Takanohana ended up even, both at 25 wins over the other. Akebono won a total of eleven championships and was a runner-up on thirteen occasions — coming second to Takanohana seven times and once to Wakanohana.

Perhaps Akebono’s career-defining moment was in 1998 when he was selected as the man to represent Japan and perform the Yokozuna dohyō-iri (ring entering ceremony) at the Winter Olympics opening ceremony.

Akebono retired from sumo in 2001.

Asashōryū

The fierce-eyed Mongolian, Asashōryū, rose quickly through the sumo ranks, reaching the second highest rank of Ōzeki less than three years after his professional debut in 1999.

Using his aggressive style of sumo, full of forceful shoves and powerful throws, Asashōryū won his first top-division championship in Fukuoka in 2002 while Takanohana was plagued with injury.

Takanohana retired in the following January. And, in a changing of the guard, Asashōryū claimed his second consecutive title, granting him promotion to Yokozuna — becoming the first Mongolian to reach the rank at the age of 22.

For the next few years, Asashōryū dominated sumo, losing only six bouts of ninety in 2005. His 2005 performance also made him the first wrestler to win all six Grand Sumo Tournaments in a single calendar year.

It wasn’t until 2006 that Asashōryū would encounter a true rival. While out injured during the May tournament, a young Mongolian — Hakuhō — won his first top-division championship.

Less than a year later, the pair would meet in a playoff for the championship title. Asashōryū was justifiably confident: he’d never lost a playoff. The match lasted for a second. Asashōryū’s grin after the match shows that he’d found his rival.

Hakuhō took the championship in the following tournament, too, earning his promotion to Yokozuna. The Mongolian pair became fierce rivals for the next few years. From 2007 until Asashōryū’s premature retirement in 2010, the pair took every single championship except two.

Asashōryū left sumo with a total of 25 championships (fourth all-time) under his belt.

Hakuhō

Hakuhō was the most recent wrestler to dedicate a stone at Kushida Shrine after his 2012 championship win in Fukuoka.2

After Asashōryū’s retirement in 2010, Hakuhō continued to dominate the sport, winning 63 bouts in a row from January through to November, eventually losing to Kisenosato just a few bouts short of the all-time record. And he continued to dominate for more than a decade.

Despite missing out on the consecutive win record — much like Chiyonofuji decades before — Hakuhō broke almost every other record possible. And they’re unlikely to be challenged anytime soon. His list of achievements firmly places him as the greatest of all time in a sport with ancient history:

- Most career championships (45)

- Most undefeated championships (16)

- Most consecutive championships (7, tied with Asashōryū)

- Most wins (1187)

- Most wins in a calendar year (86 out of 90 bouts in 2009 and 2010)

- Most tournaments ranked at yokozuna (84)

And the list continues.

Hakuhō won his final championship title in 2021 with a perfect 15-0 record after returning from knee surgery. On the final day of the tournament, Hakuhō’s final opponent, Terunofuji, earned promotion to the highest rank, becoming the 73rd Yokozuna.

Hakuhō carved the kanji 夢 yume meaning ‘dream’ on the bottom right-hand side of his stone himself.3

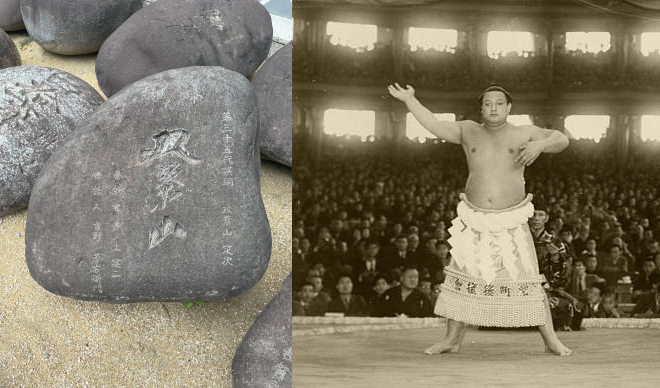

Futabayama

While Hakuhō is considered the greatest sumo wrestler of all time, he never managed to break the consecutive win streak record. The man who owns the record is Futabayama, a wrestler described as having a calm and graceful demeanor and one of Hakuhō’s heavy influences.

Futabayama set the record of 69 consecutive wins back in 1939. At the time, there were only two Grand Sumo Tournaments per year, meaning Futabayama went unbeaten for three years! In the process, he won five straight championships, got promoted to ōzeki and then yokozuna, and earned himself the nickname “The God of Sumo”.

During Futabayama’s streak, the public’s excitement caused the Sumo Association to extend the number of days per tournament from 11 to 13 and eventually to 15 — where it currently stands today.

The God of Sumo’s win streak was finally broken by future Yokozuna Akinoumi, but only after Futabayama (who was blind in one eye) fell ill with dysentery. Had he been healthy, who knows how many more bouts he would have added to his record?

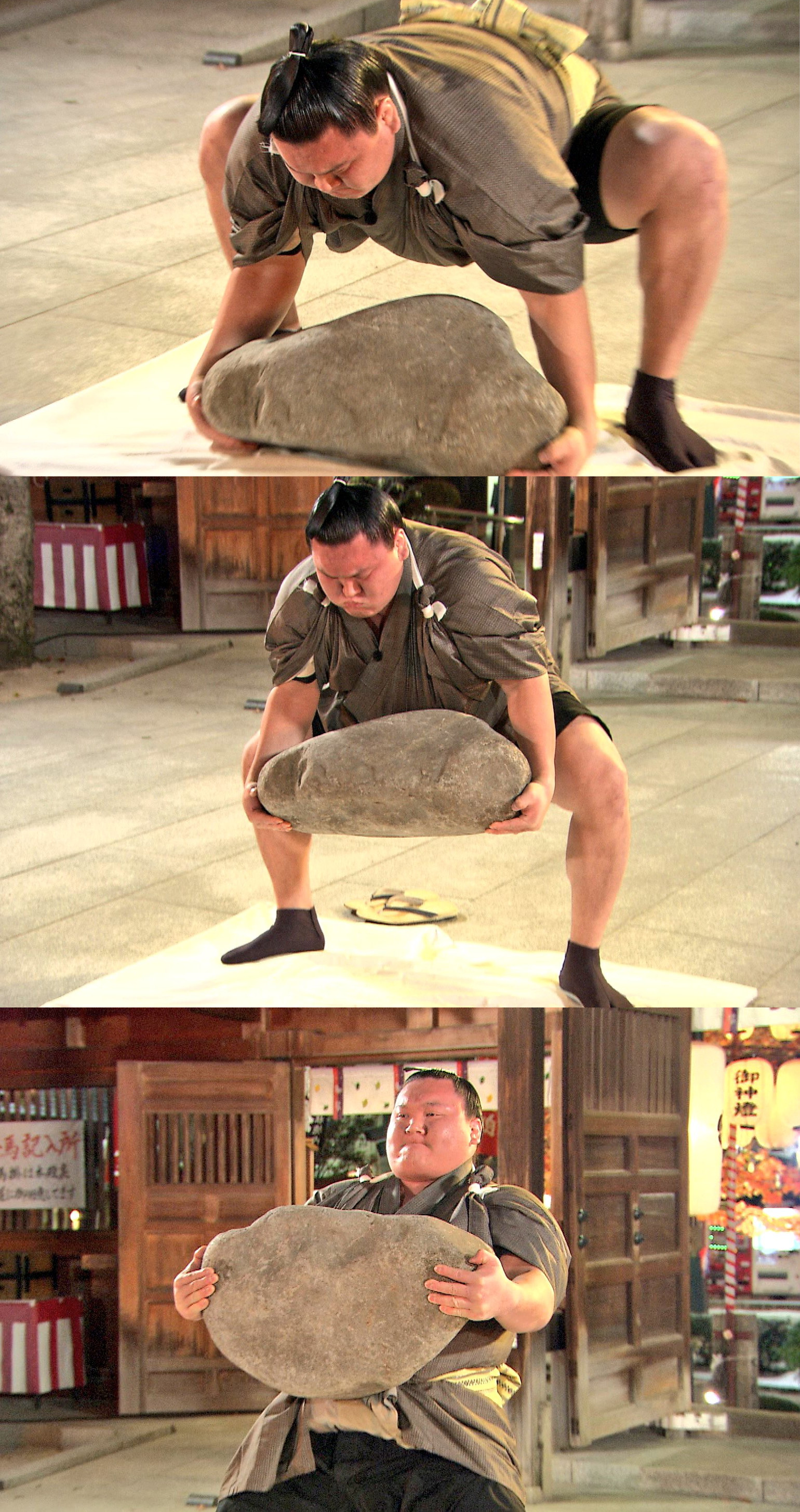

試石 — Test Stone

Understandably, with stones dedicated by sumo royalty, people were itching to compare their strength at Kushida Shrine.

So, on the ground, right in front of the platform displaying the power stones, lies a stone engraved with 試石 tameshiishi, meaning ‘test stone’, or ‘trial stone’.4

The test stone invites anyone who wants to try lifting it to compare their strength against some of the strongest sumo wrestlers to ever live. It weighs around 100kg (220 lb), so it’s not quite as heavy as the huge stones on display. But it’s a fun challenge for the shrine’s many visitors.

Lifting the test stone is a little more challenging than it first appears; the stone is super smooth, awkwardly shaped, and unbalanced, making it harder to get a good grip.

Like Hakuhō, bringing the test stone to your chest marks a good lift. And lifting it to your shoulder is a bonus!

If you do challenge the stone, you’re sure to get an audience of shrine visitors to cheer you on — ガンバレ!

Location

Kushida Shrine is easily accessible from Kushida Shrine Station (N17) on the Fukuoka City Nanakuma subway line.

The power stone display is near the shrine’s southern entrance, right next to the impressive festival float display; the exact location is on the map.

All of the power stones dedicated by sumo wrestlers are NOT for lifting. However, the designated test stone on the floor happily awaits challengers.

If you do decide to test your strength, be mindful that you’re at a Shinto Shrine. Consider purifying yourself at the purification font and praying at the main shrine before lifting the test stone. Remember to be extremely considerate of other people in the area.

Glossary

chikaraishi (力石) – Traditional Japanese “power stone” or “strength stone” used to test strength.

tobiume (飛梅) – Flying Plum, the name of a historic sumo wrestler.

kami (神) – God, deity, or spirit in Shinto.

ōzeki (大関) – Second highest rank in sumo, often translated as “Champion”.

yokozuna (横綱) – The highest rank in sumo, often translated as “Grand Champion”.

hinkaku (品格) – Dignity, grace, and quality of character, especially as expected of a Yokozuna.

yume (夢) – Dream.

tameshiishi (試石) – Test stone or trial stone.

ganbare (ガンバレ) – A Japanese expression meaning “hang in there”, “go for it”, “keep at it”, or “do your best”.

Notes

The 172.5kg stone bears the name Tomita Kyuemon — the somen noodle supplier. It also bears the date May 1830 and “I feel good at 61”. The sign beside the stones notes that Tobiume lifted a stone at 61 in 1830. Was Tomita Kyuemon a sumo wrestler? Was Tobiume his ring name? Based on the available information, it seems plausible, but I can’t confirm it.

I believe Asashōryū likely dedicated his stone in November 2006, after his 19th championship title win in Fukuoka. I found an image dated September 2008 showing Asahoryu’s stone on display. Assuming Asashōryū dedicated his stone after a Fukuoka tournament, it’s unlikely he dedicated it in 2007 — since he didn’t participate in the 2007 tournament. He did win the 2006 Kyushu tournament, so there’s a reasonable chance his dedication took place following that win. Unfortunately, I haven’t found any references to support that.

A 2012 New Year’s Eve program featured Hakuhō dedicating his stone at Kushida Shrine. Despite a long search, I haven’t found any video clips or an archive of the show. The show is called “大晦日スポーツ祭り!KYOKUGEN2012 史上最大の限界バトル”, meaning “New Year’s Eve Sports Festival! KYOKUGEN 2012: The biggest limit battle in history”. If you find it, I’ll pay you a bounty.

References

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join thousands of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.