North Rona: Shipwrecked

Guest article by Jacob Hetherington

Originally, I set off to write the story of a stone on a tiny Scottish island. After spending countless hours researching, I’ve since become entranced with a wider story: of an island quite literally at the edge of the world, a people lost, and how stone lifting culture fits in with all of this.

Forget your false Victorian notions of “manhood” stones. Forget the pragmatic Dritvík stones of Iceland where one could improve one’s station at work. This is a story about a poetic act of remembrance created through stone lifting in Gaelic culture.

Crash landing

Alexander MacLeod1 could likely hardly believe his luck when he set eyes on Ronaidh an t’haf, or Rona of the Ocean, in 1698, a tiny green island in the Atlantic. He had left Hiort (the Gaelic name for St. Kilda), destined for home on Harris, when a mighty storm raged around his open boat, blowing them more than a hundred miles off course.

His excitement was likely soon muted, as landing on the shores of the island wrecked his boat. Things soon turned from bad to worse, when he discovered that the island’s whole population had recently perished.

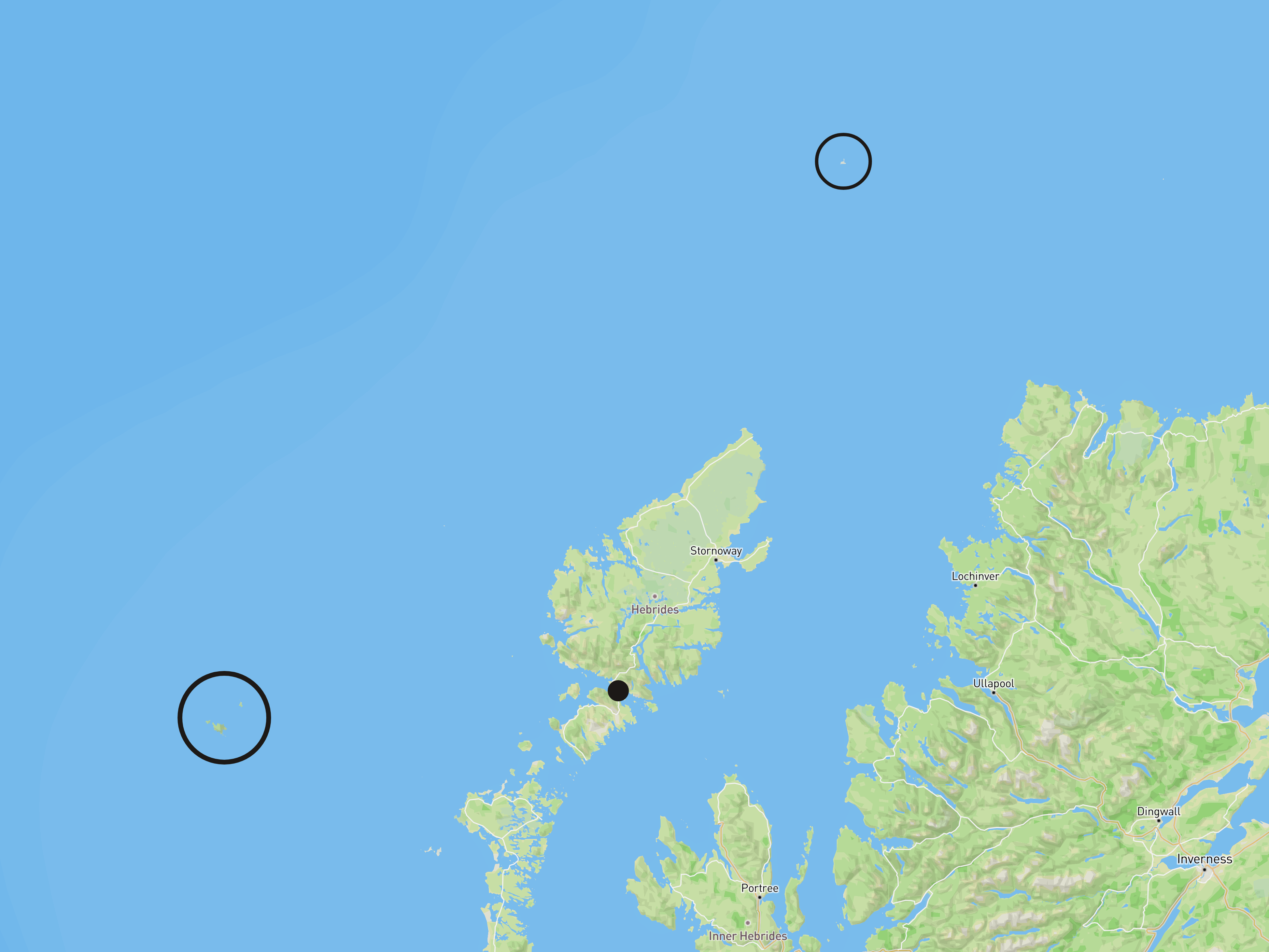

Over three hundred years later, Rona (often described as North Rona, as surveyors in 1850 were desperate to be able to distinguish it from the Rona off the coast of Skye) is just as devoid of human life as it was that day when Alexander MacLeod set afoot, as is Hiort, where he had been performing his duties as the island’s steward and tacksman.

Rona: A long inhabited isle

Rona is an island of two histories — from its earliest habitation to the day Alexander MacLeod set afoot in the late 17th century, and then till the last permanent inhabitants left in 1844. Rona either comes from “Hraun-ey”, the old Norse for “rough island”, or from St. Ronan, as one story goes that the first inhabitant of Rona was an Irish monk and his sister who sought to live a quiet life in hermitage as was often the custom of St. Columba monks at the time.

It is claimed that this first settler is responsible for the oratory, Teampall Rònain, a two chambered cell that was expanded during the island’s inhabitation to feature an attached chapel, to better provide a space for worship for the island’s inhabitants. The oratory dates to the late 7th / early 8th century, and the chapel is described as early medieval. However, there is ongoing archaeological debate which suggests it could be a Norse construction from the 12th century. A firm “first” date for habitation hasn’t been set, and cereal grain has been dated to 600 AD using radiocarbon dating methods2.

The tiny Christian oratory is apparently the best preserved of its kind in Scotland. Dating back to a similar time is a peculiar stone cross, now kept in a church in Ness (located in the north of the Isle of Lewis). The head of the cross features three holes, and on the “front” of the cross is the carved outline of a man, the holes appearing at his neck and armpits. This man’s genitals are clearly exaggerated, some sort of reference to fertility perhaps. Early descriptions and reports of the cross conveniently miss out all references to the figure, focussing instead on the holes and its shape. This artefact would appear to be some sort of merging of pre-Christian and Christian beliefs on Rona.

Little else is known of the first stage of inhabitation on Rona, as perhaps one would expect from an island so remote before the modern age. One of the best descriptions we have is from a Protestant minister, Reverend Donald Morrison, in the 1680s. It should be said that he was visiting an island that had been Catholic — forever as far as the religious knowledge of Rona goes. Esteemed Ness folklorist (and one-time resident of Rona) Angus Gunn states that the first people on Rona were “na papanaich”3 — the Catholics, and that they had strange names unlike any in Ness.

The visiting Reverend Morrison wrote of their surnames: “they take their surnames from the colour of the sky, rainbow, and clouds.” He said he was warmly welcomed but a little perturbed by some of the customs, such as their wish to bless him by walking around him “sunways” (a wish he denied, to their disappointment). He was shown inside the chapel dedicated to St. Ronan, where he saw lying on the alter a wooden plank “about ten feet long, every foot has a hole in it, and in every hole a stone4, to which the natives ascribe several virtues… One of the stones was particularly effective in promoting speedy delivery to a woman in travail”. Reverend Morrison wrote that they repeated the Lord’s Prayer and Ten Commandments in chapel every Sunday, giving a picture of a community that was still just as religious as the early monastic settlers.

These descriptions clash with those of Archdeacon of the Isles Dean Munro, who in 1549 wrote that the people of Rona were “scant of any religion”, likely a reflection that their own twist on Christianity forged by centuries of isolation on a tiny island, wasn’t to his liking.

Returning to the friendlier Morrison, he writes of a welcoming community, who were well stocked with barley, oats, cows, and sheep from the fertile island, and lived a life bereft of money or purchases. Their relative comfort was belied by the size of the community, numbering just 30: five families of six — a number that was tightly maintained. If a child was born and did not “replace” someone else, someone would have to move to the “mainland” of Ness, to maintain the population at 30. Such were the rigours on a self-sustaining remote island.

We’re fortunate that Morrison visited when he did because a mere handful of years later, we catch up to where we started: with Alexander MacLeod attempting to make his journey back to Harris. Whilst MacLeod’s fateful visit to Rona marks the end of the “first” story of Rona, it marks the start of the story of a stone.

From bad to worse

MacLeod’s unintended journey to Rona likely could’ve been described as nightmarish, blown so far off course in a storm in the large and inhospitable Atlantic Ocean. However, upon sighting land and managing to make landfall, his descriptions tell us that the nightmare continued.

As the party made their way up the slopes, they came to the remnants of the village, discovering the fate of the villagers.

Martin Martin writes:

by making farther search through this House they found a woman dead, and a child dead close to her breast, with his mouth set on his dead Mother’s breast

A swarm of rats had made its way to Rona somehow and consumed all the crop, leading to the dire fate of its inhabitants. This story is corroborated by several natives of Lewis in addition to MacLeod. Whilst the origin of the rats is unknown, a nearby shipwreck would seem to be a likely cause.

The rat’s ghoulish victory appears to be short lived, for they were not present when MacLeod arrived and not mentioned as living on Rona since. Perhaps they were too successful for their own good and followed the fate of the islanders? Maybe a mixture of crop failure, disease, and vermin could all be responsible for the “native” population’s demise?

To quote Martin Martin once more:

Occasioned the death of all that ancient race…

MacLeod lived on Rona for seven months, relying on a steady supply of driftwood “by the providence of God” to use both as fuel for fires and for the carpenter amongst the crew to begin the task of building them a boat to return home. They survived by eating the grain they had aboard the ship and the fertile, “so very prolifick” land, where he described most of the ewes and cows as giving birth to two offspring at a time. MacLeod was convinced this phenomenon would result in his wife soon giving birth to twins.

When April came, and the winter weather subdued to the calmer, brighter spring, the party left Rona, sailing south, landing in Stornoway on Lewis. Their arrival was, as one imagines, a complete shock. And upon reaching home, the feasts and celebrations lasted “for some days”. MacLeod clearly had quite the story to tell and doubtlessly many questions to answer. One such question came from the Lewis factor, Mr. Zachary MacAuly, who asked:

Did you do anything whilst you was in that Island? To keep in remembrance the mercies which you and yours have received…?

To which MacLeod replied:

I did nothing, to keep my captivity in mind to those who may land there successively after this — only I left a lump of stone on the top of another stone and with this designation, say ‘McLeod’s lift…

I edited MacLeod’s response from Michael Robson’s complete history of Rona for brevity. The full response involves promising his as-yet undelivered child to be a man of God and join the clergy if he is a boy.

There we have it, the first recorded lifting stone on Rona, dating to the last few years of the 17th century. Robson goes on to further describe ‘McLeod’s lift’:

It was also said “that this stone aforesaid, McLeod’s Lift at Rona, no man was able to lift this stone since McLeod left it at Rona. It is called Fhear-Irt’s Lift — or his ‘Ultach’”. The ‘St. Kilda Tacksman’s Lift’ is not known today, and perhaps the weather has toppled the upper stone, but, fortunately, Mr MacLeod’s wish to commemorate his adventure through his son and his stone can still be fulfilled through the re-telling of the tale.

The act of stone lifting as a tool for remembrance is clear, from MacLeod stating it was a marker of his time on the island, to Robson in 1991, writing that even if the stone is gone, it is remembered. One assumes that the fact it wasn’t liftable by anyone else was a large part of this — this was no mere pebble!

I can speak as much Gaelic as I can Mandarin, so I hope I use this word correctly: This was fraigalchd — an ostentatious display of strength.

The fact no other man was able to lift MacLeod’s stone suggests that others did indeed try. You may be asking, if the inhabitants were all deceased upon MacLeod’s arrival, who was there to try lift the stone? My wife — who has practically heard of every stone ever, through no choice of her own — suggests that his boat crew could have tried.

Stones are a permanent feature of the landscape, unlike the fleeting nature of human habitation. Alexander MacLeod’s feat created an artifact and a story that persists far beyond the people who dared to live in such a remote place.

A stone to lift?

As MacLeod’s accidental arrival marked the end of the first act in Rona’s history, soon after started the second. Much of Robson’s book focusses on this second act, which started with another tragedy — six families were sent to live on Rona and soon after lost all their men at sea, forcing them to soon return to Lewis.

From this point on, Rona was only inhabited by a single family, or occasionally a solitary man or woman. They would live there for usually up to seven years before moving back to Lewis to be replaced by another family. These people lived as tenants on the island, taking care of the sheep and producing crops and products as rent to Ness. These peoples, who mostly came from Ness, not far from Taransay and Harris where MacLeod lived, would’ve been the ones to try the stone if it ever was attempted.

The use of the word “Ultach” in Gaelic stone lifting nomenclature is surprisingly intricate and contextual5. All the known Ultach stones exist in the Inner and Outer Hebrides, and this stone certainly does not buck that trend — for Rona is about as far away from the mainland as you can be, lying closer to the Faroes than Edinburgh!

The word Ultach also means an armful or lapful — so in terms of a stone, it would be a descriptive word for something large! Befittingly, all the existent Ultachs are all very large stones — the three Ultach stones on North Uist all weigh north of 180kg (396 lb)! If this pattern were to continue, there’s no doubt MacLeod was a strong man, and no other man who lived on Rona since could match his feat. We’ll look at the manner of this feat later, as it appears to buck the trend of what one might consider a “traditional” Ultach lift.

It’s at this point where I’ll mention that whilst Robson refers to Alexander MacLeod as living on Harris, the folklorist Alexander Carmichael (writing in the 1800s) says that MacLeod was originally from Skye and lived on Taransay (an island just off the west coast of Harris, which now also lacks human habitation).

I visited Taransay in August 2023 on my trip to the Hebrides to search for Ultach Mol Na Mircein. I believe I found this stone, which is now sadly broken (an outcome that seemed the most likely with the source I had).

I believe Ultach Mol Na Mircein would have been existent in the days of Alexander MacLeod. He was a man of renowned strength, and certainly not one afraid to lift a stone — did he lift Ultach Mol Na Mircein to test and display his strength? It would not be the wildest assumption.

As Robson’s book is the definitive and sole account of the history of Rona, it is perhaps no surprise that scant else mentions this stone, and what references exist to it appear to be a messy mix of referencing each other and inventions. In the 400-page document that is “Transactions of the Gaelic Society of Inverness, Volume XLI 1951-1952”, there is a retelling of the whole account. And, as with Robson, Martin Martin is quoted as the source of the story. We’re told that Martin was personally acquainted with MacLeod and given a rough date of 1689. Much of the tale is the same, we’re told that MacLeod was:

An immensely strong man and he accordingly lifted a very large stone and placed it on top of another.

A blog post by the island-focussed blog Scottish Islands Explorer in 2013 tells the tale, asking where on North Rona is the stone, asserting that Martin Martin published the story in 1703 and that the stone is still existent. I’ve seen no evidence of either. Martin did indeed publish “A Description of the Western Islands of Scotland” in 1703, and it does cover MacLeod’s visit to Rona, but no mention is made of the stone. The edition I’m reading, however is the second edition published in 1716, so the possibility of a change in editions does exist. As to the assertion that the stone still sits atop its “plinth”, I have found no such evidence — albeit absence of evidence is not evidence of absence!

Peter Martin’s Twixt the Stone and The Turf 5 also states the stone is still in situ. However, Peter Martin was usually meticulous in finding and documenting of stones, and no other (published) works of his reference this stone. Certainly, his book was clearly not finished, as we only have access to the first half. A trip to Rona is a significant undertaking, and as a man who was searching for stones across Scotland, it likely would have been lower down on his priority — so I am confident that his belief in its existence is based on the other sources I have mentioned, and not concrete evidence.

So, where does this leave us? Our interest in “Ultach Fear Hiort” is more than purely academic. The goal would be to set foot on Rona, find this stone of remembrance, and, if possible, lift it, recreating the act of Alexander MacLeod over three hundred years past.

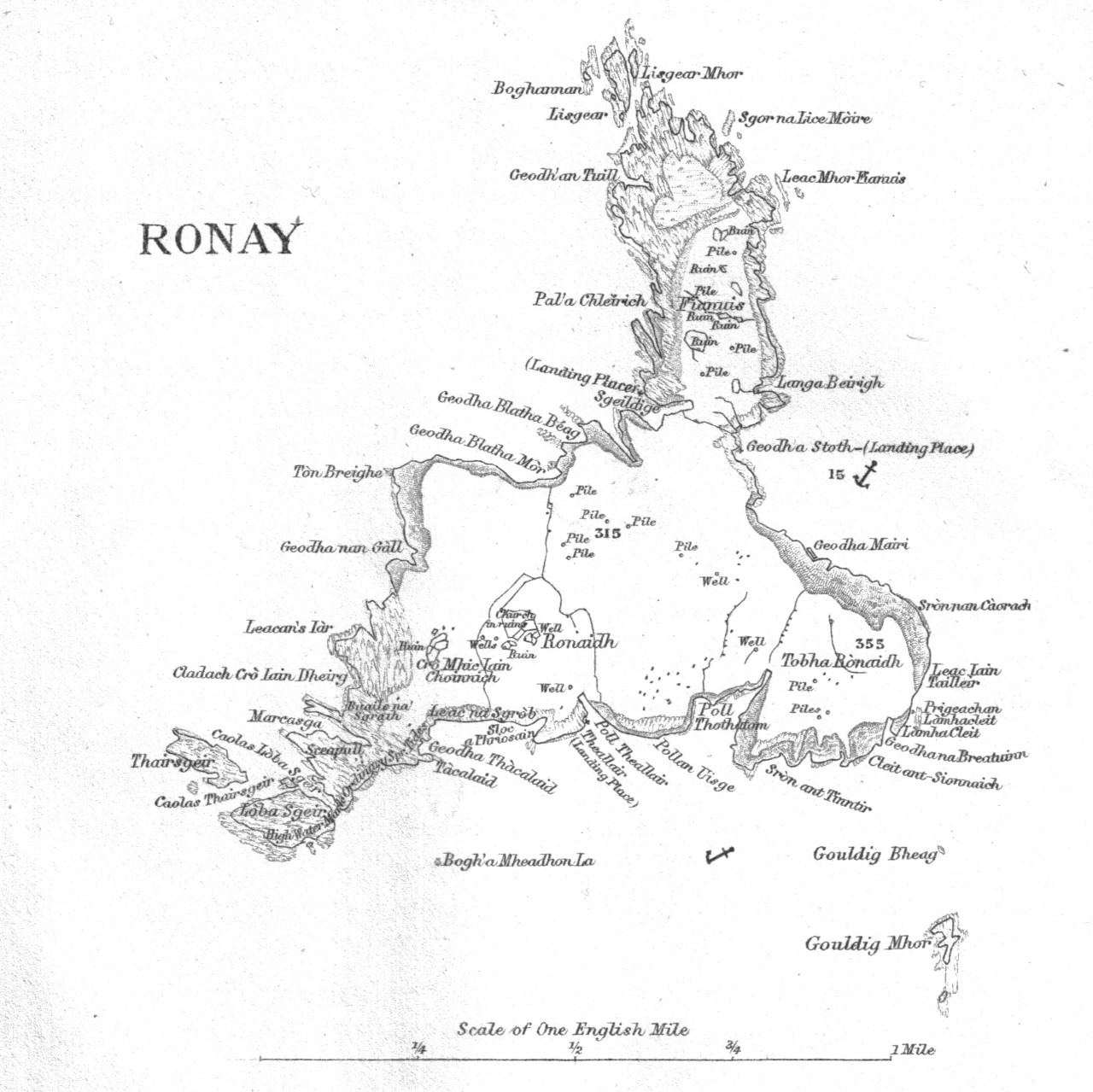

Robson states that the stone is not known of, which seems likely given not only the length of time that has passed, but also the lack of any large or even continued habitation. Much of the habitation post 1700 was iterant — not exactly conducive to passing down tradition. Robson’s work does include an impressively detailed map of Rona, with nearly every cliff being named, suggesting that a high level of knowledge was maintained. However, there is the high possibility that the placenames of Rona were different from those of the original population pre tragedy, as they likely had no way of informing anyone of their landscape and landmarks.

I’ve scored over many visitors’ photos and YouTube videos of Rona, looking for clues or suspicious-looking stones that could indicate the stone’s location, but have naught to show for my time. The descriptions of the stone, a huge stone atop another, or a rock ledge (as per Peter Martin) are likely going to create very few candidates for the stone. So, from that point of view, the challenge is easier — it’s not going to be like finding three stones and trying to guess which one it is!

This fact that separates this “Ultach” to every other known Ultach — none are atop plinths, or even the kind of stone most would consider putting on top of a plinth! Excepting tales of pressing a huge Ultach overhead on North Uist (Ultach Dhomhaill Mhoir), a traditional lift would likely be “to the lap” or simply just “putting wind under the stone” owing to their huge size. The idea of putting such a stone on a plinth is no simple undertaking.

Could the wind have blown the stone off? Robson’s book contains an account from the naturalist Darling on the topic of storms. And he told of how the northern strip of Rona, Fiannus, becomes “an inferno” as the waves crashed over the steep cliffs across the land, “still sufficient force to roll boulders up and down which may weight anything from a hundredweight to two tons…”6 Thankfully for us stonelifters, the inhabited part of the island is much higher from the sea and protected from such waves.

When Dr MacCulloch visited the island in 1819, meeting the MacCagie family who inhabited the island at the time, he was surprised to see that they lived in a “subterranean retreat” whose entrance looked more like the mouth to a cave, barely three feet high and covered in turf. No doubt, this was a home designed to withstand the worst the weather could throw at the island.

In 2011, Cyclone Berit hit much of North Europe, including the Faroe Islands, with reported wind speeds of up 123 mph (198 km/h). In Harris, a woman sadly passed away as her car was blown into a loch. There’s no doubt the wind can be a destructive, powerful force, and three hundred years is ample opportunity for the stone to be blown off. It’s easy to dismiss the idea of a mere gust blowing the stone off its perch, but I think it’d be ignorant to ignore this as a possibility. If one assumes that the stone was blown off its resting place atop some sort of plinth, it may still be lying beside it, making for an easier identification.

Human activity could be another factor — we know many of the ruins over time have been disturbed for one reason or another, be it hunting for bird’s eggs or building alternate structures, such as the sheep pens at Fiannus to the north of the island. However, a stone so large no one could lift it bar MacLeod seems a poor choice to use for your project from an effort standpoint! Rolling a stone or pushing it off is far easier than lifting it, so it remains a possible reason the stone no longer sits atop it’s plinth.

Until such a day as one goes to Rona with the express purpose of finding Ultach Fear Hiort, the mystery of the stone’s location or existence shall remain.

A trip to Rona requires a four-hour boat trip north from Lewis, with good weather essential. Once the journey to Rona is over, one must make the precarious landfall sprightly, for there is no bay or sheltered landing area to make the task easy. From there, the search begins, so pack your hiking boots and be prepared to move, as your time on the island is often limited by the necessities of the homeward trip. And if the weather is to indicate a poor forecast, the search time may be cut short.

Of course, to solely focus on the stone would be remiss. You’d be stood on a speck of green, surrounded by the vast blue Atlantic Ocean — land that was once people’s homes for generations hundreds of years ago. No other land in the UK can claim to be so remote yet still someone’s home.

Stone lifting is more than a physical activity; it’s a cultural one, and to ignore the culture of Rona, to not scramble into the cell that a holy man once built to get closer to God over a millennia ago, would be missing the wood for the trees.

The stories of stones on Rona don’t end there. There’s actually more than one stone to find, and indeed, there’s reason to believe that you’re probably not the first man (or woman) to lift any stone on Rona that you fancy lifting…

In part two, we’ll take a deeper look at the iterant tenants of Rona and one such tenant named Iain, who was very fond of two things that are particularly close to my heart: stone lifting and whisky!

Oh, and of Alexander MacLeod’s pregnant wife — it wasn’t twins after all, but a healthy boy, who did indeed become a Reverend. And he’d keep the story of his father’s trip alive, telling people he was conceived on Rona of the Ocean.

Author

Jacob lifted his first historic stone back in 2017 and has been hooked ever since. His passion for uncovering lost stones has lead to the discovery of Scottish and Icelandic stones. If pressed for a favourite, he’d pick the Ardvorlich in Scotland, Leggstein in Iceland and Cloch Chaladh an Uisce in Ireland.

Notes

-

A brief note on “MacLeod”: throughout this article you will come across both “MacLeod” and “McLeod”, both referring to the same gentleman. Any discrepancy is purely down to source materials. I have endeavoured to stay consistent with the sources and not change such spelling differences for the sake of spelling. The reason it is spelt both ways is beyond me! ↩

-

Rona The Distant Island by M.Robson 1991, pg 20 ↩

-

In 1938, Naturalist Frank Fraser Darling spent three months living on Rona with his family to study the seal population. Whilst there he rebuilt the now collapsed chapel, attempting to restore it to its former shape using photographs from the 1800s. Whilst digging inside, he found a large, polished stone of green marble on the right-hand side of the altar, after digging to expose the full size of the altar. (Robson, pg 134). Was this stone one of the original stones from the descriptions of Morrison? It seems far too much of a coincidence to be not… ↩

-

Twixt the Stone and the Turf, Peter J Martin, via thedinniestones.com ↩ ↩2

-

Rona The Distant Island by M.Robson 1991, pg 133 ↩

Read the liftingstones.org letters

Join hundreds of other stonelifters who read the world's most popular stonelifting newsletter.